|

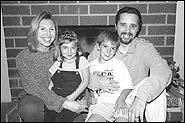

Worth the Risk QUINCY IS A WOMEN'S STUDIES STUDENT IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA. She and her husband have two children of their own - and scattered around the world are six more babies made with Quincy's genes. She's been a surrogate mother and an egg donor. The first time she donated eggs, they were fertilized with a German man's sperm. A surrogate carried the pregnancy - triplets - and the resulting babies went to the man and his wife in Germany. Quincy has never seen the children. She says she's "curious about what they look like," but "you don't long for their children because you know they wouldn't be a family without you." Quincy says she offered to be a surrogate mother and then an egg donor because "I've had two healthy babies, so why shouldn't someone else? I have the right looks, the right genes." She says her children were "so cute and so smart and so fun, somebody else should have one just like these guys." She checked into the possible complications before she donated eggs, but "I thought it was worth the risk in order for other people to have babies." Quincy says she wasn't after money. When she first called the center, she didn't know she could get paid. She points out that the center won't accept donors who are on welfare. The women receiving eggs through the center do tend to be wealthier than the women who donate eggs, but "most of us don't have serious money issues," Quincy says. Whatever the concerns over the health risks and the potential of coercing donors with high fees, egg donation is a growing business. More than 10,000 donor babies have been born in the last decade; some are already in grade school. And the number of donations grows each year. But Helane Rosenberg of IVF New Jersey doesn't envision a future in which donor babies are as commonplace as adopted children. Rosenberg believes in the future, fewer women will wait until they are too old to try to start families. She says she frequently talks to women who had no idea that if they waited until they were in their late 30s or 40s, after they established careers, they would be less likely to conceive. "I hear about it all the time: the generation that forgot to have children," Rosenberg says. "I don't think we're going to have that [in the future] because I don't think this generation of 30-year-olds is going to forget to have children." Someday, new technologies may even make egg donation largely unnecessary. Researchers are working on ways to freeze human eggs. So someday, it may be possible for a woman to freeze her own eggs when they're young and healthy and then use them years later, when she's ready to have children. The Decision to Donate home |