By Lynette Nyman

March 10, 1999

|

||

| Part of This Is Home: The Hmong in Minnesota |

Traditionally, when Hmong families bury their dead, they dress them in

hand-sewn clothing. The basic designs are old; Hmong culture has been traced

back more than 5,000 years in China. While living in refugee camps in Thailand,

Hmong women continued their hand-stitching. Aid workers took notice. Soon this

private work was re-fashioned for a foreign marketplace. But the work is becoming

harder to buy as Hmong women find easier ways to earn a dollar. In this part

of our series on the Hmong, efforts to revive the tradition may be no match for

the demands of making a living.

HMONG STITCHING IS SOME OF THE FINEST and smallest

human hands can make. It's incredibly precise and the tiny details can strain

the eye. But such needlework won't be easy to find any longer. After 17 years

in business, Corrine Pearson finally closed her "Hmong Handwork" store

in Saint Paul. Before locking the doors, Pearson worked her way down the list

of Hmong women whose work she's sold.

Pearson: And I'm wondering if some of the things you've had here, that have been here for a long time, if you want to lower the price?Since 1981, Pearson has sold - on consignment - the work of Hmong women who resettled in the United States after leaving refugee camps in Thailand, and that of those who stayed behind. Several years ago, the last of the refugee camps closed, and so did the main pipeline bringing Hmong needlework to the U.S. from overseas. Here, Hmong women's lives have changed a lot since they first arrived. Pearson says the older Hmong women - those in their 60s, 70s, and 80s - complain of poor eyesight. The women in their 30s, 40s, and 50s don't have the time. And Pearson says the youngest women and girls aren't learning how to sew.

Pearson: They're in America. They need dollars-per-hour. They need income. They need employment. And this kind of work doesn't provide any kind of reliable income. It doesn't provide anywhere near enough money because it all depends on whether a piece was sold. And there are not enough hours in the day or the week or the month to sew enough even if everything was sold to make money to live on.

|

|

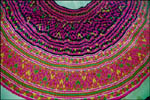

| Traditional Hmong Skirt | |

| See See larger view |

Masami Suga, with the Refugee Studies Center at the University of Minnesota, has conducted oral history projects with Hmong sewers. Suga says the Hmong tradition had women teaching girls to sew as early as four or five years old. She says they started with a very small piece of cloth.

Suga: Barely larger than the size of their hand. And they would learn basic cross-stitching. They'll learn the combinations of certain colors. They'll learn different types of different patterns. And eventually, by the time they're somewhere between 10 to 15 years old, the girls knew how to do needlework but were also able to complete and sew an entire ensemble.

|

|

| Scene from Hmong story cloth. | |

| See See larger view |

Lee: Not many Hmong people are doing it. They are saying "why do you waste your time doing, it takes like a month to make one, when you can go to work and make five, six dollars an hour?" But for me, because I can't work and I don't have anywhere to go, I make it because when I get lonely. It makes me happy to do this. It brings me happiness.Some Hmong students at Harding High School in Saint Paul are getting ready for their Hmong-language and -culture class. This lesson is on Hmong sewing, one recent effort to preserve the craft.

MPR: Are these traditional Hmong colors or different? Do you know?

Lee: I don't really know. I guess so because I've seen almost every elder. They've been using these colors for a long time, so it must be traditional. I don't know if they got any new colors right now.Student Cher Lee was born in Thailand, but has lived in the United States since he was three-months old. Lee says as a young boy he watched his mother and sister sewing at home. But like other Hmong boys, he didn't sew.

Lee: I didn't know anything about the Hmong traditional patterns until I was in sixth grade, then I started learning about Hmong culture and stuff like that. I kind of realized this is my culture.Lee's pattern is four little squares on a piece of cloth the size of a bookmark. He's using pink and green with blue in the middle. He learned the pattern from one of the Hmong elders who teaches in the Hmong Textile Arts Project funded by the University of Minnesota's Extension Service. The women elders earn $10 an hour for coming to the class a few times each week. Doua Lee has been sewing for over 30 years. She's got some samples of her work in a plastic bag. The threads' bright colors leap off the cloth.

Lee: The reason I come here is because I know that I have very good experience doing this kind of stuff. And I know that I need to pass on to the Hmong, the young generation, and I don't want this to disappear.Doua says she's happy at the school while sharing her culture. It's a chance for her to get out of the house and to see the world Hmong children live in. Despite efforts like hers, the sewing tradition is still endangered - in America at least - as the Hmong become Hmong-Americans and the tiny stitches fade into the past. Photo Credit: Masami Suga