By Mary Losure, Minnesota Public Radio

September 10, 2001

| Real Audio |

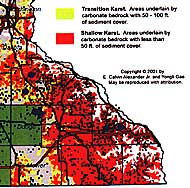

Much of the rolling, picturesque farmland of southeast Minnesota is is what geologists call "karst." The soil is underlain by cracked, water-soluble rock, riddled with underground tunnels and caves. That makes the region's groundwater highly vulnerable to pollution. Depressions, known as sinkholes, can appear without warning when the underlying rock collapses. Sinkholes act like drains, whooshing water - and contaminants - into underground aquifers.

Now, many local residents are worried as large, industrial-scale feedlots begin to move into the karst region.

| |

|

|

|

||

Bob and Eloda Wood are retired dairy farmers who do volunteer monitoring of the south branch of the Root River in southeast Minnesota. It's one of the state's best trout streams, and flows through Forestville State Park.

Each week, the two drive the winding road from their farm to the stream to collect samples. On a recent day, Eloda Wood pointed out the sinkholes, disappearing stream valleys, and other classic karst features along the way.

"They tell us that much of our surface is like Swiss cheese, and wherever there is vertical crack, that's an invitation for a sinkhole," she says.

So the Woods were alarmed when they learned of plans to build a factory-scale feedlot, the Reiland Dairy, just up the valley from Forestville State Park.

The dairy's earthen-lined manure lagoons would hold more than seven million gallons of manure. If a sinkhole opened up under a lagoon, the Woods and other opponents worry that all that manure would flow into the groundwater. From there it could gush through underground rock tunnels into the Root River, and devastate both it and Forestville State Park.

"Instead of just flooding with water, it would be flooding with manure," Bob Wood says.

A University of Minnesota karst expert characterized the feedlot's risk as "enormous." Both the state Department of Natural Resources and the state Health Department expressed serious concerns, but the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency ruled the project could go ahead.

Opponents, including the Woods, took the PCA to court - and won. In December, a Fillmore County judge ruled the agency had neglected its duty by failing to consider the catastrophic level of water pollution a sinkhole collapse might cause.

| ||

But PCA officials still insist the project could have gone ahead safely. "That was our decision and is still our decision," according to Beth Lockwood, the supervisor of the agency's environmental review program. Lockwood says the agency evaluates only environmental impacts that may be "reasonably expected" to occur from a project, and in the agency's judgement, a sinkhole breach was too remote a possibility to consider.

"We did not feel that after the engineering was all designed, and we looked at the project as a whole and how it was designed and engineered, that we reasonably expected a catastrophic release to happen," according to Lockwood.

The PCA did not appeal the judge's decision, and proposers of the dairy decided to move it to another area. But it's likely more lagoons will be proposed in the karst region, as as dairy farmers there expand their operations. That could cause problems.

Manure lagoons have caused massive water contamination in North Carolina, the state where they were first widely used. They are now banned there.

Minnesota has banned them for hogs, but still allows them for dairies.

In Minnesota's karst geology, dairy manure lagoons are permitted as long as there are no more than four sinkholes within a 1,000 feet and the bedrock is more than 10 feet down. In addition, lagoons may not be built within 300 feet of any sinkhole. Hog manure pits must be lined with cement.

If they meet those regulations, the only thing stopping big feedlots in the karst is local opposition. And that isn't always as effective as it was in the Reiland case.

"We're right in the middle of three big outfits," laments Kermit Burt, whose parents own Burt's Hilltop Poultry, a small poultry processing plant surrounded by a large turkey farm and two industrial-scale hog operations

Now the Burts worry about their well. "What's going to happen if our well does suddenly shoot sky high in nitrates and we've got to replace it? Who's going to cover it?"

The Burts and other neighbors fought hard against the most recently built hog feedlot. Until this summer, they thought they'd stopped it.

The feedlot was not large enough to require mandatory review by the PCA, but the county board had denied it a permit because it would sit in a high-risk karst area.

| |

|

|

|

||

But this June, neighbors like Dale Pierce learned it was going up anyway. "We thought that because it was all denied by the county officials and even the state Court of Appeals, that it would not go any further. But then they changed the way animal units are counted, and one person was able to approve the permit, and we've got the building now and we can't do a darn thing about it," says neighbor Dale Pierce.

A little-noticed change in the county's regulations had put the proposed feedlot just under the size limit for environmental review by the county.

Bobby King, an organizer for the family farm group The Land Stewardship Project in Lewiston, says with the weakened county regulations, there's not much they can do. "Now we're relying basically on the PCA to look out for a facility that size to make sure it's safe. And we know they're not doing the job," King says.

But others, like State Sen. Kenric Scheeval, R-Preston, say blanket opposition to big feedlots in karst terrain is misguided. The area has traditionally been home to small-scale livestock operations, and Scheeval if such farmers can't expand , they'll get out of the livestock business. He says that would mean hilly terrain that's traditionally been used for pasture, would be plowed up and planted in row crops like corn and soybeans, which would greatly increase soil erosion.

"Frankly, a lot of those hills will end up in our waterways, because farmers are going to use their land; they're not going to just idle it. They're in the business of producing either crops or livestock," Scheeval says.

Scheevel says large feedlots can be built safely, as long as they're properly located. "There is a certain level of risk to anything you build in the karst region," he says, "but you can also map out the sinkhole plains, and you find that there are regions in which the sinkholes tend to follow a specific pattern. You get away from those sinkhole plains, and the risk of a sinkhole opening up is probably minimal, if not almost irrelevant."

But others are not convinced the risks are minimal, especially if more and more factory-style farms move into the karst region.

The State Health department has asked the PCA to develop guidelines for emergency response plans in the area to handle possible catastrophic spills.