By Jeff Horwich

Minnesota Public Radio

October 24, 2001

|

| RealAudio |

The architect I.M. Pei once said that if it weren't tucked away in rural Minnesota, the St. John's Abbey Church in Collegeville would be one of the 20th century's most famous pieces of architecture. Today the church turns 40. Four decades after its dedication, the controversial design still leaves visitors both awed and repelled. But the church remains just as loved as ever by those who brought it here.

| |

|

|

|

||

In May of 1958, St. Cloud architect Ray Hermanson was beginning the most important project of his young career.

"When the construction started, I was out there every day, for a full day," he said. "I used to drive out in the morning and have lunch with the monks and some of the construction crew."

Thousands of tons of concrete were to be poured into a church and bell tower like nothing Minnesota, or the Vatican, had ever seen. Despite the massive scale and the progressive nature of the design, Hermanson says construction went off without a hitch.

| |

|

|

|

||

"I would think it was a pretty significant project, but everything went well," he said. "The forms and everything were put in place, and the steel was put in place, and everything went according to order."

Hermanson was the on-site representative of the famous Hungarian-born architect Marcel Breuer. Breuer was a disciple of the German Bauhaus school of design. He came up with a concept for the monks at St. John's that some have called "brutism," which featured giant structures of rough, unadorned concrete surfaces with a sampling of local granite.

"Natural" and "honest" buildings, to use the Benedictine spin.

Father Vincent Tegeder, who ran the abbey archives before he retired, says the monks didn't set out to be daring. They simply needed more space for the growing abbey and the students at St. John's University.

| |

|

|

|

||

But they moved boldly ahead when Breuer returned with a design that was destined to shake things up.

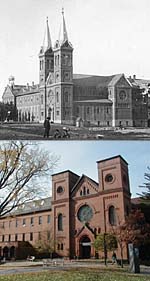

There was some controversy over what's called "the banner," a flat slab of concrete rising 112 feet directly in front of the church. When this new bell-tower went up, the building committee and the architect decided the twin towers of the old church would have to come down.

"It might have caused a distraction, shall we say, from the banner," Tegeder said. "So the banner now is the symbol of St. John's."

The north face of the church is one of the largest walls of stained glass in the world. 430 colorful hexagons of abstract design. In a church of 1,400 seats, the monks had achieved remarkable intimacy by breaking with tradition and placing the altar in the middle of the floor. The building found international acclaim, but there were complaints from some local Catholics that the church was just too brutal, too different.

| |

|

|

|

||

"Oh, there were some negative reactions in the community, but overall it was quite satisfactory," said former Abbot John Eidenschink, the chair of the building committee. "I think it still holds all its original power."

This week, most passing students had nothing but affection for this concrete giant that dominates the landscape on their way to class.

"I would say like "massive," maybe, that's one of the first words that comes to mind," said David Soren, a sophomore. "I do kind of get a solemn impression from it, though."

"My first impression was that it was too big, too cold, too concrete," said Katie Corbett, a senior. "But going here for four years I've completely learned to love and appreciate how it is totally unique for the world in terms of architecture and things like that. I've definitely come to like it much more and it's a more holy place to me now."

| |

|

|

|

||

"It's kind of neat. When I'm coming back from home, it's like, well there's the church, you know, I'm almost there. It's like a homecoming, a calling-type thing, I guess," said senior Noah Hummerding.

Today's festivities will honor the church and designer Marcel Breuer, who passed away in 1981. Local architect Ray Hermanson will be here, too. Forty years ago he was walking this ground nearly every day with the plans for this church under his arm. This time there's nothing to do but stand back and look.