By Rob Schmitz

Minnesota Public Radio

October 25, 2001

|

| RealAudio |

Fifteen miles south of Wabasha lies the Weaver Bottoms, a 4,000-acre wetland fed by the Mississippi River. The region was home to the Midwest's most diverse array of vegetation and animal habitat. It has since lost that title. But one man studies one species in a fight to keep the Weaver Bottoms, and the the river, alive.

| |

|

|

|

||

Number 57 crawls through tall grass, looking for a place to hibernate. The turtle retracts his slender neck as Mike Pappas picks him up. His number, painted white on his black, concave shell, helps Pappas identify him in the wild. Number 57 is an old friend - Pappas first caught him 21 years ago. As he coaxes the turtle's head out of his shell, Pappas's proud smile looks almost fatherly.

"I've known him for a long time," says Pappas. "He knows me by the way he's looking at me."

Mike Pappas has independently trapped and studied turtles in the bottoms since 1974. A restaurant owner from Rochester, he has turned a hobby into a crusade. Nearly all of Minnesota's 10 turtle species are here in the Weaver Bottoms. One of those is the Blandings turtle, a threatened species. In the 1970s and '80s, Pappas trapped and studied more than 2,500 Blandings turtles.The study attracted national attention and now, federal and state agencies have hired Pappas to study all the turtles in Weaver Bottoms. The early findings confirm what Pappas already suspected - the Blandings turtle is being wiped out.

"Of the 1,200 turtles I've caught in the Weaver Bottoms this summer, I've only caught 10 Blandings turtles, and they're all older turtles like this one. That says to me that there's not much recruitment - there's no habitat for the younger hatchlings and juveniles," says Pappas.

Pappas says the culprit is flooding in the Blandings' marshy habitat. In the early 1930s, the Army Corps of Engineers built a series of locks and dams that flooded large areas of the river's floodplain. These areas quickly became highly productive backwater marshes with dense vegetation. That was a typical response from a floodplain, where embedded seeds sometimes wait years for water in order to sprout. However, beginning in the 1960s, aquatic vegetation disappeared due to a lack of water fluctuation, reducing the marshes to what are now open, windswept lakes.

| |

|

|

|

||

Wearing swimming trunks and old tennis shoes, Pappas guides his flatbottom boat into the Weaver Bottoms. Three times a week, Pappas makes these runs around the bottoms to check hoop traps. During the summer, he can catch up to 25 turtles in each of these six-foot by three-foot traps. But as autumn takes over, the turtles dig into the sediment to hibernate. Pappas arrives at one of the traps. He kills the motor and jumps into the chilly, waist-deep water.

"There's something in this trap. I don't know if it's a turtle or a fish," he says as he pulls the trap out of the mud. "There's a couple of turtles and a couple of carp - about 30 pounds of carp."

The trap holds not only carp, but also two painted turtles. Pappas will weigh and measure the turtles. He'll drill identification holes on the edge of their shells. The turtle species Pappas finds tell the story of Weaver Bottoms. A river backwater that's becoming a lake.

"I think 75 percent of the 1,200 turtles I've caught are the pond-type turtles, which is really significant. That's showing that this is really becoming one big pond - a reservoir or lake - versus the 25 percent that are the faster current-type turtles. There should be more."

Pappas pulls out some color-coded aerial maps. They're from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They detail the land of Weaver Bottoms.

"Just look at the colors, that's all you have to tell. This is before they flooded it."

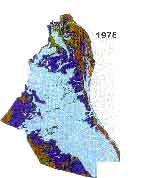

Each of the four maps details a different year, from 1891, before the locks and dams, to 1989. Colors - green, brown, orange and blue - show different types of ground cover and vegetation.

"So this was a diverse area - marshes, uplands, open water. Then you go to 1940, right after they flooded it, and it became pretty good. The dark blue is good, and so is the green. But this is not good," Pappas says as he points to the light blue on the map.

| |

|

|

|

||

He scrolls through the map pages, showing how much that color increases over time. Light blue indicates open water - not something that's natural in a wetland.

"Then you get over here - 1975, 1989 - you can just see how the color is going out of the picture. It's just getting worse and worse and worse," says Pappas. "It's amazing that it went from here to here to here. And 1989? We're in big trouble."

In the 1960s, vegetation started to disappear, and a vicious cycle of environmental damage began. Phragmites, a tall cane that protected the bottoms, died out, creating a marshland unprotected from the wind. The wind stirred up sediment in the water that destroyed submerged vegetation. In 1986, the Army Corps of Engineers built two islands in the Weaver Bottoms. Their intent was to reduce wind damage and restore vegetation. A report 10 years later said despite millions of dollars in so-called improvements, the project actually increased erosion in the bottoms. Mike Kennedy owns property near the bottoms. He says setbacks like these are typical of an agency that focuses on navigation, not the environment.

"I've seen a resource that should be managed as a balanced resource managed as strictly a commercial resource of navigation," says Kennedy. There's some big things wrong in high levels of government, where the lobbying of large multi-national corporations can outdo anything the public wants, and that's sad. There's some companies like Cargill and ADM that make a hellof a lot of money off the Mississippi River, and myself, you, and the public are financing their profiteering. I don't like that."

"I don't think we're sold out to big business, but they have to understand that it's a multiple-use resource out there," says Dennis Anderson, a fisheries biologist for the Army Corps of Engineers.

Anderson agrees it's important to consider the river's many roles. This summer, the corps reduced water levels near La Crosse while maintaining navigation. The result was positive - more vegetation. Anderson thinks the same is possible for rehabilitation of Weaver Bottoms, but he adds an agreement on a reduced water level will require a lot of compromise.

"I'm sure it'll be a negotiated thing, deciding what level it'll be at. We'll be balancing that factor between increased maintenance dredging, increased access problems, and the amount of area we can expose versus the various levels of drawdown," Anderson says.

For those who've studied Weaver Bottoms, a compromise may not be good enough.

Back at Weaver Bottoms, Mike Pappas takes a break from checking traps to take in the scenery - the bright, white color of hundreds of pelicans feeding nearby is a sharp contrast to the murky-colored water.

"I was brought up with strict religion, but this is more my cathedral now than that ever was, because of it's totality. I become a part of it," says Pappas. "You can't be out here without feeling the power. Just look at the sun, the waves - it's beautiful."

Pappas is still an optimist. He hopes the damage done to Weaver Bottoms can still be reversed. He wants to help restore this, his cathedral - along with its dwindling parish - in his lifetime.