Photos

More from MPR

Your Voice

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The budget mess: How we got here

March 12, 2003

|

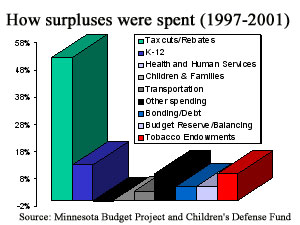

| Of the total surplus dollars allocated in 1997 through 2001, more than half were spent on tax cuts and rebates. (Data source: House Fiscal Analysis) |

St. Paul, Minn. — In December 1999, then-finance commissioner Pam Wheelock told reporters the state had a "boatload of money" when she announced a $1.6 billion projected surplus. A year later, Wheelock said the projected surplus had ballooned to $3 billion.

"Today I'm here to tell you that we're busting at the seams, and the challenge for the stewards of this ship is to make sure she continues to be seaworthy," Wheelock said then.

Internet stock was flourishing. People were working. Wages were good. Interest rates and inflation were at historic lows.

Even so, finance officials were sounding a note of caution.

"This forecast is risky," said state economist Tom Stinson. Stinson said in 1999 that the state's revenue forecast included very optimistic predictions of economic growth. He said any downturn in the economy would reduce the surplus. All it would take, Stinson said, is for the good times to not be as good.

Less than a year later, terrorists flew planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the stock market boom was over - and the nation's economy plummeted. "Who could have predicted Sept. 11?" Wheelock said. She noted Minnesota relies heavily on income and sales taxes, the areas that are most affected by changes in the economy.

"So as the economy weakens, people lose their jobs, their hours get cut back, they don't get the bonuses that they expected, which is turning out to be a much more significant factor today than even, you know, five or six years ago, and their capital gain is diminished," Wheelock said.

State economist Stinson says Minnesotans' capital gains plunged from $9 billion in the year 2000 to $4 billion in 2001.

Like many other states, Minnesota spent much of the boom years cutting taxes and raising spending. In all, from 1998 to 2002 about $7 billion was sent back to taxpayers in rebates and permanent tax cuts. The state's unique three-party government system led to a three-way budget fix in 2000, with the surplus being divided between new spending for education promoted by Democrats who controlled the Senate, permanent income tax cuts pushed by Republicans in the House, and a cut in fees for vehicle registrations championed by Independent Gov. Jesse Ventura.

In 2001 Ventura and House Republicans pushed for a dramatic restructuring of Minnesota's complex property tax system. The plan had the state take over the basic cost of education. It lowered rates on commercial-industrial property and higher priced homes.

Overall it will cost the state's general fund about $1 billion per year. Ventura sold it with a promise of statewide property tax reductions averaging 15 percent. That happened in 2002, but an analysis done by the state Senate in 2003 shows that homeowners will actually face average increases of about 15 percent this year...all but wiping out the cuts from the reform.

By 2002 Ventura and lawmakers were facing a $2 billion shortfall. Ventura called for $700 million in spending cuts, $400 million in tax increases, and using more than $600 million of the state's budget reserves.

The House, led by Republican Tim Pawlenty and the Senate, led by DFler Roger Moe, rejected Ventura's plan and eventually passed their own plan to balance the budget, overriding Ventura's veto. Their plan cut some spending, but also borrowed money and emptied a variety of reserve funds to avoid raising taxes. Both Pawlenty and Moe ran for governor in 2002. Later, Ventura decided not to run for re-election.

While Moe and Pawlenty campaigned, the economy got worse. In November, shortly after Pawlenty won the election, state officials announced a $4.5 billion dollar shortfall projected for the 2004-05 biennium.

While much of Minnesota's deficit stems from lower tax collections, part of the problem is higher spending, particularly on education and human services. Half of the education increase is from the property tax reforms of last year, and much of the human service spending comes from rising demand for state-funded health care programs.

Pawlenty, who ran on a pledge to not raise taxes, says the trends demonstrate Minnesota has a spending problem.

"This idea that spending's going to go up in the next biennium 14 percent, which is what's projected, 14 percent, when the money coming in the door is only going up six or seven percent, the math just doesn't work," Pawlenty said. "And somebody needs to get in there, and it's going to be me, and say, we need to learn to live within our means and that means resetting priorities."

|

News Headlines

|

Related Subjects

|