|

Audio

Photos

More from MPR

Your Voice

|

Less is More (Work)

August 17, 2003

|

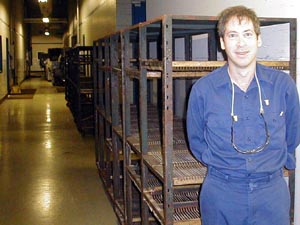

| Empty circuit board racks show the depth of the slowdown at iFlex, where Brian Golob is environmental health and safety manager. (MPR Photo/Bill Catlin) |

St. Paul, Minn. — "You notice the lights in this hallway are off," says Brian Golob as he walks down a darkened corridor. "It's just another cost-saving measure," he says, turning into a nearly deserted room filled with long rows of machinery containing chemical baths. Golob is the environmental health and safety manager for iFlex, a Minnetonka company that makes printed circuit boards.

| |||

"Two years ago in this room, aside from the humming of the fans, the exhaust fans and the equipment, you would hear people's voices, talking to one another. And as we stand here today, you don't hear the human voices," Golob says. "There's just one or two people in here, so all you hear is the background noise of the machines operating."

Golob says a downturn in the circuit board industry has decimated the company's workforce. iFlex co-owner Craig Bergman says several years ago, the plant employed more than 300 people. Now there are a few more than 30.

"Three years ago is when our industry saw the downturn start, really as a result of the dot-com implosion, if you want to call it that. In the North American circuit board industry, there were roughly 900 circuit board companies like ours," Bergman says. "That has come down rather dramatically where I think the latest estimates are in the 300 range."

| |||

Bergman says his company is hanging on, waiting for an upturn and hoping to survive long enough to capture business from competitors that have gone under.

For Brain Golob, that means more duties, filling in for people who've been laid off.

"I spend probably 50 percent of my current time split between two other jobs, working in the lab as the lab tech, and fulfilling the role of my former hazardous waste technician.

One guy. Three jobs.

"But everyone needs to wear multiple hats in order for the company to survive," Golob says.

He has a master’s degree in environmental health. But on this day he is sporting the blue pants and shirt that come with the hazardous waste technician duties. Earlier he was washing out 55-gallon drums.

| |||

"I'm not sure I went to graduate school to wash drums,” he says. "But it's one of the things I can do here, so..."

He gets help with his extra duties from other employees. But as his work has expanded, his time to get it done has been cut in half.

"One of the cost saving measures from the company's perspective was to ask the managers that are here, and I'm considered a manager, to basically work every other week. And we've been on that schedule for several months. Which adds to one's stress level, and makes for a difficult household financial situation also," Golob says.

Combined with a prior pay cut, Golob’s salary is down 60 percent. For now, he's the sole breadwinner in his family. His wife is a computer consultant whose work has dried up.

"It's difficult wondering if I'm going to be gainfully employed in a month, or two or three. There's a dim light at the end of the tunnel that we can see. The question is, 'Can we reach it or are we going to fail?' From a daily perspective of working here, there's additional stress, just because there's so many little things that have to get done on a daily basis, so it makes the job a little bit tougher," Golob says.

| |||

To get all that work done, he essentially volunteers his time for the company. This is technically his week off, but he's at work.

"I've probably put in the equivalent of 100-plus hours as a volunteer. I'm not the only one. There are other folks around here who have done that too. If I wasn't optimistic about the company's survival, I wouldn't be willing to do that. But I've been trying to contribute when I'm getting paid, and when I'm not getting paid, there are these environmental and safety issues that still need to get done, and I don't want to ignore the employees that are here," Golob explains.

Despite the double whammy of more work and stress, but less pay, Golob describes iFlex as, "a good company," and the senior management as "good folks." He says the more jobs an employee can do, the more value to the company, the greater the job security.

"You can become demoralized, and think you're spiraling downward, or you can be grateful that you're still gainfully employed. I try to take the attitude that I'm still gainfully employed, even though it's not full time right now. My present situation is certainly better than some of my friends who are unemployed," Golob says.

For Michelle Beckrich, the workweek didn't shrink; it nearly doubled when slowing sales led to layoffs.

|

It went from the typical 50 to 60 hour week to the 70 to 80 hour week, to writing speeches at two o’clock in the morning

- Michelle Beckrich |

"It went from the typical 50 to 60 hour week to the 70 to 80 hour week, to writing speeches at two o’clock in the morning," Beckrich says.

She was a marketing executive for a company that sells goods and services to the workforces of other companies. She doesn't want to name the firm. Amid what she calls the "downsizing of America," the company's sales fell. Her department's job was to help get them back up.

But about a year ago, her department laid off about half its staff. More cuts followed in the fall. Beckrich says the need for marketing remained, along with her own drive to succeed and help the business.

"You continue to just take on more and more and more. As your people are becoming more stressed, and you can see it either [physically] or displays of behavior, you say, 'You know what, I'll just handle that. I'll just stay tonight and I'll get that spreadsheet done, or I'll take these 6 calls; you take those," Beckrich says.

The work followed her even when she was taking time off.

"On vacation, I mean, you're still hooked to your cell phone. And the cell phone rings and you find yourself four hours later and a dead battery talking to either the employees or the bosses or customers. That gets to the family. The family will come and say, ‘I thought we were going to go boating.’ It's like, 'I'll be right there, I'll be right there, I'll be right there.' All of a sudden, four hours later, it's starting to rain," says Beckrich. "Never got boating."

Beckrich says the pressure and stress became tremendous, the workload unmanageable. Sleep, exercise, and self-esteem suffered.

"By nature, I'm more of a perfectionist, but I found myself [saying], 'Whatever--get it out!' And so you start cutting your own standards down. At a certain point, you stop on the quality aspect and you just go for getting it out, getting it out. And then you're judged on the mistakes."

Beckrich says she didn't have time to notice the toll it was all taking until, as she puts it, she had time to come down from being glued to the ceiling. That came in April, when she too was laid off.

| |||

"I found myself sleeping and taking naps for three months; slept 11 hours a day, then took naps. I didn't realize I was so tired. And yes, I've seen my doctor a few times."

In some ways, Beckrich says, the timing was fortunate. Her husband still has a job. Her eldest son graduated from high school this spring, and is off to college. And despite the pressures, she loved the work.

"I don't regret it. But now I look back--I've had a little bit of time to take some time out, and I say, 'Boy, I was a driven work nut.' I know they appreciated it, found my performance excellent, and outstanding, but here's what I have for it," Beckrich says.

August brings the start a new job-hunt, and new expectations for her next employer.

"I'm going to look for signals of balance. For example, a CEO who says, 'You know, it's four o’clock. We've got to wrap this up by four-thirty. My kid's got a ball game.' I'm going to be looking for those things that in the past I hadn't looked for."

Beckrich is aiming for a position in the health field, one of the bright spots in the job market. But as American companies learn to adapt with fewer employees, some observers are wondering whether the jobs that are lost are gone forever, ratcheting the demands of the workplace a few notches higher.

|

News Headlines

|

Related Subjects

|