|

Audio

Photos

Respond to this story

|

Blackduck company recruits Latino workers to fill labor gap

December 27, 2004

Anderson Fabrics in northern Minnesota, is the largest maker of custom drapery products in the country. It's located in the small town of Blackduck, a half hour north of Bemidji. Because of its geographic isolation, the company has struggled to find the skilled workers it needs. Company officials think they may have found a solution in the Twin Cities Latino community. Nearly 40 Latino workers moved from the Twin Cities to Blackduck this fall. The company says that's just the beginning. Blackduck school and community leaders are now bracing for what's expected to be a wave of Latino families. But a housing shortage in Blackduck could slow down the migration.

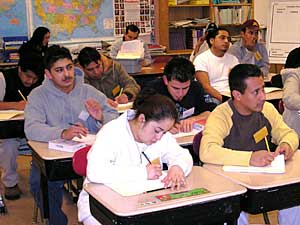

Blackduck, Minn. — Blackduck's population is only about 650 people. The town's population has dwindled in recent years. So has school enrollment. No one here expected the turnaround would come from Latinos. Since October, the Blackduck Community Education classroom has been full of the town's new Latino residents eager to learn English. They're all Anderson Fabrics employees hired through a Twin Cities employment agency.

Most of the new arrivals are Mexican. But they also come from Peru, Guatemala, Brazil, El Savador. Francisco Matalo is from Equador. Speaking through an interpreter, Matalo said he never expected to find himself in a northern Minnesota town.

"I like Blackduck," said Matalo. "The nature is beautiful. There are many lakes. And the people are very relaxed."

| |||

Like many of the newcomers, Matalo left his wife and kids back home. He'd like to become a U.S. citizen and start a new life in Blackduck.

"We've spoken about this with my friends, my co-workers," he said. "And I'd estimate that about 70 percent of us would would like to stay here, bring our families here."

That's good news for Ron Anderson. He started Anderson Fabrics 25 years ago with just a handful of workers. He now employs nearly 400 people.

But turnover remains high, about 45 percent. Anderson struggles to find and keep skilled employees. He's tried to lure workers from about a 50 mile radius of the plant. But not everyone is willing to travel so far for a starting wage of $9 an hour.

At one time, Anderson was so desperate, he considered moving part of his plant up to the Red Lake Indian Reservation, where unemployment is typically more than 50 percent. It would have included daycare and a training center. But Anderson abandoned the plan because of concerns over absenteeism among Red Lake workers.

"The people coming from the reservation are very talented," said Anderson. "It just seems like they're not on, for lack of a better way of putting it, on the same time clock as we are. They work out for a few weeks or a month or so, and then the absenteeism starts and the problems start."

Anderson says his labor shortage problem will soon become critical. He's taking on some new customers next year that will require the business to grow. Anderson says he's convinced Latino workers are the answer. He expects their numbers to grow to 100 or more next year.

When Anderson first set his sights on the Twin Cities labor market two years ago, it wasn't the Latinos he turned to. Anderson worked with a Hmong employment agency and hired about 30 Hmong workers. He purchased seven mobile homes for them to live in.

| |||

"We filled up the mobile homes practically overnight with the Hmong community," said Anderson. "But it didn't work out for the community, it didn't work out for the school district, and it didn't work out for us. The culture was too different."

Blackduck community leaders say there was, indeed, a culture clash. The arrival of Hmong workers was sudden, no one in Blackduck spoke their language and only a few of the Hmong spoke English. With relatively little warning, the school district had to create an English as a Second Language Program for about two dozen new Hmong children.

Ward Merrill is director of Community Education in Blackduck. Merrill says only a few in the group were interested in learning English or integrating with the community. But he says the community probably failed to reach out to help them.

"Truthfully, I think we kind of missed the boat with the Hmong population," said Merrill. "There probably was a sense of prejudice and preconceived ideas about what would be the impact of Hmong people in a community. There did not seem to be a positive feeling from the get-go with the Hmong."

| |||

The Hmong workers at Anderson Fabrics lasted less than a year in Blackduck. Tou Ying Lee worked for the St. Paul agency that recruited them. Lee says the workers felt isolated because they're more accustomed to living in larger Hmong communities.

"I think the problem is the people who our organization sent to work there, they don't speak English very well," said Lee. "If they stay there, they need somebody to help them. And the Hmong people, they tend to live close to their relatives. And in that way, they get more support from the relatives."

Blackduck community leaders say things are different with the new Latino workers. They say it's probably because Hispanic culture is more familiar to local people. Many have taken Spanish classes in high school. They cook Hispanic foods in their homes. Some vacation in Mexico.

Many of the new Latino workers are trying hard to learn the culture of northern Minnesota. Participation in community education programs has quadrupled since they arrived. Along with English classes, they're taking courses in hunting and fishing regulations and job skill development. They're getting help navigating the process of becoming naturalized citizens. In the coming weeks, they'll get a hands-on course in ice fishing.

So far, only a few children are part of the Latino group. But that's expected to change. Bob Doetsch is superintendent of Blackduck Schools, where enrollment has been declining for years. Doetsch hopes the Latino migration will help reverse that trend.

"They're tremendously hard working people and they want to do well," Doetsch said. "I just think for us, it could mean opening a new classroom, which would be wonderful, adding another teacher, opening another ESL program, maybe adding more Spanish. The Latinos coming up could mean all sorts of benefits for the school."

| |||

Ron Anderson feels confident his custom fabrics plant may have solved its labor shortage problem. But he says there's an even bigger problem looming.

"All of it is going to depend on housing," said Anderson. "That is the critical thing. If we don't get the housing, we're going to be stymied, and the growth for this company that we're taking on is going to be done in some other state by themselves. We won't be doing it."

Anderson has donated land to develop 18 rental town homes and possibly a subdivision of 20 to 40 single family homes. But it's not likely to happen without help from the state.

Arlen Kangas heads the non-profit Midwest Minnesota Community Development Corporation in Detroit Lakes. Kangas says the number one problem facing rural communities is how to provide affordable housing. He says that problem will intensify as new immigrants to the state filter out beyond the Twin Cities.

"Certainly I think the wave is coming," said Kangas. "The state's responsibility certainly is to assist communities like Blackduck. The question is, are they going to have enough money to take care of all of the priorities that they see."

|

Finding people now won't be a problem, because Latinos, we go where there's work... We're sort of like moths attracted to that light out in the dark.

- Doris Ruiz, manager of Olen Staff Company |

The number of Latinos in Minnesota more than doubled from 1990 to 2000. Most live in the Twin Cities. Doris Ruiz manages the Twin Cities employment agency that brought Latino workers to Blackduck. Ruiz predicts Latinos will find their way to more small towns in rural Minnesota.

"We are, without meaning to, causing a ripple effect, causing a change, causing the regular white inhabitants of rural Minnesota to, maybe a couple of years from now, go into the Mexican store to by cilantro and chili peppers," Ruiz said. "Is this going to stop? No, I honestly can say, no."

A few years ago, Ruiz brought Latino workers to the town of Wilmar, where there was a worker shortage at a turkey processing plant. She says there are plenty more Latinos who will move if it means steady employment.

"Finding people now won't be a problem," she said, "because Latinos, we go where there's work, we'll go. That's where we'll follow. We're sort of like moths attracted to that light out in the dark.

Leaders in Blackduck have pulled together business owners, educators, clergy and social service workers to discuss more ways to help Latinos integrate into the community. Officials with Anderson Fabrics say they expect to hire more Latino workers in February.

|

News Headlines

|

Related Subjects

|