|

Audio

Photos

Resources

|

April 22, 2005

|

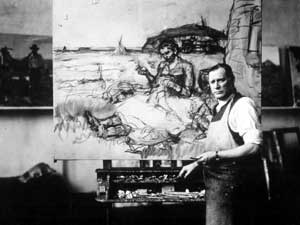

| Harvey Dunn at work in his New Jersey studio. (Photo courtesy of the South Dakota Art Museum) |

Brookings, South Dakota — Most of Harvey Dunn's best known works are housed at the South Dakota Art Museum in Brookings. It's not far from where Dunn was born in 1884, on a homestead farm. Those were pioneer times, some of Dunn's neighbors still lived in sod houses, the plow turned up buffalo bones and fierce winter storms isolated people for weeks. Standing in the Harvey Dunn gallery, museum director Lynn Verschoor points to Dunn's best known work, "The Prairie is my Garden".

"People drive from all over and if that painting is not up, we have a lot to answer for," says Verschoor.

The paintings sense of history and heritage is one reason so many people drive to Brookings to see the original. It captures the opportunity and danger homesteaders faced more than a century ago. A pioneer woman stares over the prairie. One hand holds a freshly cut bouquet of flowers, the other pointedly shields her children from some unexplained danger.

From normal viewing distance, the picture appears as fresh as when it left Dunn's easel. But get close, a couple of feet, and the remains of a crack can be seen across the top. The crack was delicately filled about a decade ago. It was the first restoration work on Dunn's art, but demonstrated the need for more. Nearby is a work repaired recently. It's a 1928 painting based on Dunn's time in France during World War I. Curator Lisa Scholten says the painting was riddled with cracks.

"They were large enough you could see into it to tell that the paint had separated from the canvas," Scholten says. "The painting itself really was in jeopardy of being lost forever. Because you could have had rather large chunks of paint fall from the surface of the painting."

Dunn's technique is one reason the picture needs work. The oil paint is almost an inch thick. Stand close and the colors undulate like waves on a lake. That's a lot of weight hanging on the canvas. Walt Reed is writing a book about Harvey Dunn. He says the lavish use of paint is emblematic of an artist who lived big in every way. The New York based artist and businessman still clearly remembers the one time he met Dunn.

"The most immediate thing that everybody took away from their first meeting with Dunn was being impressed with the huge size of the man. And his powerful physique. He looked more like a prize fighter than an artist," says Reed.

Reed says Dunn attacked the canvas, troweling on the paint. Six feet two inches tall, barrel-chested, Dunn's figures are as robust as he was. Pioneer women muscling there way through daily chores, pumping water or stretching barb wire. An old farmer with hands like fence posts, the tines of his pitch fork bent from the force of his labor. The paint is thick, but filled with detail.

Few Dunn paintings are ever sold, since most are owned by the state of South Dakota. No one knows what a major Dunn work would bring, but some lesser, privately owned pieces have sold for as much as $100,000. Reed says Dunn earned a living as a magazine illustrator, drawing for publications like the Saturday Evening Post and Harper's. But Reed says Dunn is best remembered for a series of South Dakota based works which brought him virtually no money. They're known as Dunn's "prairie paintings".

"Well, I think those are his finest pictures," says Reed. "He certainly put everything he had into them. It was a kind of recollection of his youth, painting very directly and powerfully."

Dunn created the prairie works late in life, living on the east coast, showing them only to a small circle of friends. Among the group was a newspaper publisher from South Dakota, who urged Dunn to bring the paintings back home. In a decision which sealed his legacy, Dunn decided in 1950 to exhibit the paintings in the publisher's hometown, De Smet, South Dakota. The works were praised, and Dunn decided on the spot to donate the prairie paintings to the state.

The pictures are the core of the Dunn collection at the South Dakota Art Museum in Brookings. But it also contains many other Dunn works, including World War I paintings and magazine illustrations. One by one, the art is being transferred to Minneapolis for restoration. The work is being done at the Upper Midwest Conservation Association, a company that restores all types of artwork. Senior Paintings Conservator Joan Gorman is working on an especially difficult Dunn painting.

"Untreated, it's a lost picture," says Gorman. "It really requires conservation treatment to make it once again exhibitable."

The oil painting was a magazine illustration for a war story. It shows a soldier staggering into a room to find his superior with his head down on a desk. The picture suffered heat, smoke and water damage in a fire. About a year ago Gorman tested a chemical agent on a very small part of the painting. It successfully darkened the oil paint close to it's original color.

"It hasn't reverted to that blanched, white appearance. So that I know I will be able to do that to the entire damaged area and return the picture to that very bright, very active surface for which Harvey Dunn is so well known," says Gorman.

As artists, conservators like Gorman are minimalists. They consider and test a wide range of alternatives before settling on one.

"Any material that we would add to a painting has to meet some fairly strict criteria," says Gorman. "It has to be stable, it has to have some longevity, and it has to be detectable by another conservator and completely reversible."

The goal is not necessarily to restore the picture to it's original state. A crack on a Harvey Dunn painting is a good example. If it's unnoticeable from normal viewing distances it may be left alone. It the crack is obtrusive, the conservator might add just enough paint to mask it, though it's still visible up close.

For many of Dunn's paintings the restoration work will be less rigorous, they may just need a good cleaning. Once the project is finished, most Dunn paintings may not need work for close to 100 years. That sort of longevity is what South Dakota Governor Mike Rounds had in mind when he launched the project.

"That type of work and that type of a gift has to be shared not just with this generation but with generations in the future as well," says Rounds.

Speaking from his office in Pierre, the governor keeps the artist close. Hanging on his office wall is an original Harvey Dunn painting. Rounds say it does what all good art does.

"'Something for Supper', done in the 1940's I believe, is in my office. And I have a chance on a regular basis to literally get lost in that painting," says Rounds. "Something new in that painting just jumps out at me."

Rounds says it might be noticing Dunn's use of colors or how he painted wind- blown grass. The restoration work will enhance the you-are-there sensibility in Dunn's work. It's both tribute and recognition for an artist who helped document an important moment in the region's history.