|

Audio

Photos

More from MPR

Resources

|

June 14, 2005

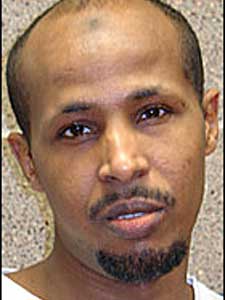

Somali Keyse Jama is a man without a country. The U.S. wants to deport him, but Somalia refuses to accept him. American governmental officials say his case is not about terrorism; they want to deport him for committing a crime in Waseca. Jama remains in the Washington County jail as he and thousands of other deportable Somalis wait for a resolution to his case.

Stillwater, Minn. — Keyse Jama's odyssey through the legal system began in a Waseca parking lot on an early June morning in 1999. Jama, now 26, who acknowledges he drank heavily at the time, fought three other Somali men from opposing clans.

Waseca police reports say Jama stabbed the men -- one in the shoulder, one in the hand, and another in the arm. Jama pleaded guilty to third degree assault. The judge sentenced him to a year and a day in jail for his crime.

Now, five years later, Jama sits in prison blues at a conference table in the Washington County jail. The jail does not allow outside tape recorders, so jail officials record our talk with Jama. Jama's attorney is present and so is a Washington County sergeant.

Jama is a slight man, his brown eyes run deep with emotion and frustration.

"I'm not saying I don't do nothing wrong. I make mistake and I accept my mistake," says Jama. "But people can change. Anyone can change."

Jama's crime meant deportation. There was a problem, however. The U.S. government had no diplomatic relations with Somalia, because that country lacked a functioning government. Without a functioning government, no government official could consent to accepting Jama.

Still, immigration officials tried to deport Jama. He appealed, and a court battle ensued for four years. In January, the U.S. Supreme Court, by a vote of 5-4, ruled the U.S. could deport Jama, departing from nearly 50 years of immigration policy.

The U.S. government hired a private firm called RMI to drop off Jama in a more stable region of Somalia known as Puntland. At least two men accompanied Jama as he entered the Puntland airport. Jama had no passport. Court documents also say a purported immigration official there asked Jama whether he had $5,000 or $10,000. Jama says he answered no.

"The Somali police chief started arguing with the guys, 'Why Americans don't bring this guy, why you bring? Then they start arguing, 'How much money you guys get?'" Jama recalls. "Everything go crazy then. There is no system, one guy talking there, another guy talking there. One guy have a machine gun and he say, 'I don't want to see you guys again.'"

Court documents say the local authorities in Somalia rejected Jama because the U.S. government did not deal with them directly. They also did not want to become a "dumping ground" for American criminals.

Immigration could try to deport Jama again, even back to Puntland. Ali Galayhd, a former Somali prime minister, says the decision about whether Puntland should accept Jama is complex.

He says Puntland officials are in a tough spot, because on one hand, they need support from the U.S. government. On the other, there is fear other deportable Somalis will be next if Puntland accepts Jama.

"There are people here in the Twin Cities who will do everything possible for that not to happen," Galaydh says. "And that would include talking to Puntland officials to create a picture that, if you allow this guy to come, there will be thousands of people who are going to be taken there."

There is another issue for Puntland, or any other area of Somalia accepting deportees -- money. Galaydh says Somalis on deportation lists who work in the U.S. send money back to their relatives and friends.

"Immigrants who are here have provided an economic lifeline for Somalia. So if thousands of them are thrown out, that is going to be an economic blow," Galaydh says.

Right now, Jama remains in jail while immigration officials figure out what to do with him.

Last month, federal Judge Jack Tunheim granted Jama's request for conditional release. Tunheim's order said that Jama would remain under supervision and possibly wear an electronic monitoring device. Immigration sought an emergency order from the 8th Circuit, delaying Tunheim's order, and won. So Jama remains in jail.

Tim Counts speaks for Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which began reporting to the Department of Homeland Security in 2003. Counts says there are myriad reasons to keep Jama locked up.

"It was inciting riots, planning and carrying out planned ambushes of fellow detainees that resulted in serious injury, continuing flooding his cell," Counts says. "Also, we are holding him because he presents a significant flight risk."

Jama's attorneys argue that Immigration has never proved these allegations. And even if they are true, they occurred years ago. Moreover, Judge Tunheim found Jama has been a model prisoner for nearly two years.

Jama's case has touched off substantial tension between Tunheim and Immigration that is noticeable in court documents. Tunheim has criticized Immigration for withholding information. In addition, Immigration misrepresented its assurance to Tunheim that, "everything was in order" for Jama's deportation.

Tim Counts disagrees with the federal judge's findings that Jama does not pose a danger or flight risk.

"It is the judgment of detention and removal professionals, who have years of experience, that he is a flight risk and that he is a danger to the community," Counts says.

Jama has mixed emotions about the United States. He says he believes Muslims are under heightened scrutiny. But he also sees hope.

"If you are Somali and you are a refugee and you come to this country, you have a lot of opportunity here. And I still believe, and I think this country is great," Jama says. "Somalia today is machine guns in the street, AK-47s, bazooka, tank around there. I go to airport and see tanks. What airport do tank?"

Nevertheless, Jama says he is ready to go. He is tired of living in Minnesota's jails.

"I don't know what to do, to tell you the truth, but I'm happy to go there to get out of this place," he says. "I will go anywhere, anywhere, anywhere I'll go."

In 1959, a federal appeals court decided a similar case. It ruled Immigration could not deport a man to China because the U.S. had no diplomatic relations with that country.

Then, the court warned that trying to drop off a deportee to a country only on the chance it would accept him could mean shuttling the person back and forth. The court predicted the same kind of problems Jama's case now presents.

Keyse Jama remains in the Washington County jail awaiting deportation that could come tomorrow -- or months from now.