|

Audio

Photos

More from MPR

Resources

|

June 28, 2005

When sex offenders are released from a Minnesota prison, they're assigned a risk level. The public is notified when Level 3 offenders, those considered most dangerous, move into a community. But thousands of sex offenders in Minnesota have no risk level assigned. That means even if law enforcement considers them a danger to the public, those offenders must remain anonymous under Minnesota law.

Moorhead, Minn. — On a late summer evening in 1986, a few people gathered for a party at a house in the Twin Cities. Before the party ended early the next morning, three men abducted a teenage girl at knifepoint. She was driven to a remote country road, raped multiple times, badly beaten, and left lying naked in the roadside ditch.

The teenage girl survived the attack. Three men were sent to prison for the brutal rape.

This story is about how the system treated two of those men.

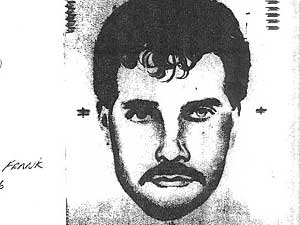

Minnesota considers Michael Allen Franson a high-risk sex offender. His picture is on the state Web site for Level 3 sex offenders. Police can notify the public anytime he moves to a community, because he was released from prison after Minnesota enacted the Sex Offender Notification law.

The other man who served time for raping the teenage girl is Michael Leo Frank. He has no assigned risk level in Minnesota, which means police can't tell anyone where he lives.

Michael Leo Frank is anonymous, because he was released from prison before Minnesota's sex offender notification law took effect in 1997. The law requires sex offenders to have a risk level assigned when they get out of prison.

Michael Frank would have remained anonymous, but in 2002 he moved to a small town in North Dakota, where he registered with the local sheriff as sex offenders must do whenever they relocate.

North Dakota officials began evaluating his risk level, and about three months later, North Dakota identified Michael Frank as a high-risk sex offender.

By then he had moved to Grand Forks, where he got the attention of local police. At the time, Officer Wayne Schull was responsible for community notification of sex offenders.

"In this case, the offender having been assessed a high risk level, we were going to do the full-blown community notification," says Schull. "(We would) post the picture on the Web site, all the things that go along with high-risk offenders," says Schull. "Based upon what I know about his criminal history, to be completely blunt, he's not a person I would want living in my community."

Officer Schull contacted Michael Frank to tell him Grand Forks police were planning a public notification meeting. He says Frank reacted angrily, insisting he was not a dangerous sex offender. "He was upset that North Dakota had actually done a risk assessment on him," says Schull. "His reaction to that indicated to me that he didn't feel responsible for the crime he'd been convicted of."

Officer Schull says the next day Frank called to say he was moving back to Minnesota, where he would not face public scrutiny.

That's when Michael Frank became anonymous. MPR tracked him to a Minnesota town. Police there won't talk about him. They can't even verify if he registered, as sex offenders are required to do.

But we know he was there, because he spent about a month at the local homeless shelter. The people who run the shelter had no idea he was a convicted sex offender. When they discovered he was having sex with a vulnerable woman staying at the shelter, they kicked him out.

Shelter officials won't talk about it publicly, and they asked that their shelter not be identified. They fear a lawsuit if they violate Frank's confidentiality.

It's unclear where Michael Frank lives now.

He's one of about 15,000 registered sex offenders in Minnesota, according to the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. About 3,000 of those offenders have been evaluated and assigned a risk level before being released from prison.

An estimated 12,000 sex offenders have no risk level because they haven't been assessed. Offenders who are sentenced to time in a county jail, probation, or those who were released from prison prior to 1997 are not assigned a risk level.

A recent change in Minnesota law allows police to notify the public when a high-risk sex offender moves here from another state.

It's likely many of the 12,000 Minnesota offenders with no risk level assigned would be considered low-risk offenders if they were evaluated. But at least 3,000 served time in a state prison and were released before the community notification law took effect in 1997.

A Minnesota Department of Corrections official says using statistical analysis, it's fair to assume approximately 350 of those could be Level 3, high-risk offenders, if they were evaluated.

Ottertail County Sheriff Brian Schlueter says the public should know more about potentially dangerous sex offenders. Schlueter was also a member of Gov. Pawlenty's Sex Offender Task Force.

"Unless you've taken an interest, or unfortunately, been affected by one of these people, I think the general public is ill-informed about how many offenders are out there and how many of them aren't locked up," says Schlueter.

Schlueter is concerned about some new studies that he says show many sex offenders commit dozens of sex crimes before they are caught. He says those studies are supported by lie detector tests that have been given to sex offenders in Minnesota.

Schlueter says he knows of sex offenders he considers a danger to the public. But all his department can do is try to watch them. They can't share information on their whaereabouts with the public unless the offender is put in the Level 3, or high risk category.

Schlueter says law enforcement should have the option to tell the public about any sex offender they consider dangerous.

"I actually think it would help. A lot of people say, 'Well, that's not fair because housing becomes an issue, because no one wants to live next to them. And who's going to hire them if you give them no chance to succeed?' And there's some argument for that because there are some people who have turned themselves around," says Schlueter. "But once you've chosen to harm someone on such a personal level, I think you give up a good share of your rights, as well you should."

Sex offenders should give up their right to live anonymously in a community if there is any evidence they may be a danger, says Schlueter, a view shared by many law enforcement officials. He says in his experience, few sex offenders change their behavior patterns.

In Minnesota there are about 3,000 sex offenders who've spent time in prison but have no risk level. That's because they got out of prison before Minnesota required sex offenders to be assessed and assigned a risk level.

That means police can't tell anyone they've moved to town, not even the homeless shelter where they live.

Gary Groberg runs Churches United for the Homeless in Moorhead, and is on the board of directors for the Minnesota Coalition for the Homeless. His shelter is not the one where Michael Frank lived after he left North Dakota to avoid public scrutiny.

Shelter staff must be suspicious of everyone, says Groberg. He says it would be helpful to have access to more information about sex offenders.

"Sure, that would make it easier for us," Groberg says. "Of course it would. Then we would be able to check against that list when people wanted to check in."

Groberg says such a change raises the question of where homeless sex offenders would go, a question he's thought a lot about. He says he hasn't come up with a good answer.

Some shelters, including the one where Michael Frank lived, say they plan to run background checks on everyone who comes to their shelter. That's not practical, according to Gary Groberg.

"We're simply not designed to say, before you can check in to our emergency shelter we're going to run a background check that might take two or three days. So even though the need may be there, it's just physically impossible for us to do it," says Groberg.

Instead, shelter staff watch closely for any signs someone might be a sex offender. Groberg says families who stay at the shelter are not allowed to leave their children alone for even a moment.

That kind of vigilance may be more effective than telling the community about every sex offender, according to Bill Donnay, director of the Sex Offender Risk Assessment and Community Notification Unit at the Minnesota Department of Corrections.

"Sure, it would be nice to notify everybody about everybody. But is that the best use of resources according to the evidence we have today?" Donnay asks. "Sometimes the focus on being notified of sex offenders in our lives is counterproductive, because if we're notified there are no known sex offenders in our neighborhood we tend to relax -- which is not a good idea, because many sex offenders are not known."

It would be impractical and expensive for the state to evaluate the several thousand sex offenders who don't have a risk level assigned, says Donnay. Those offenders were released from prison before state law required assessment and risk levels, and the Department of Corrections has no authority to evaluate them.

State law requires all sex offenders to register with law enforcment, so police know where offenders like Michael Frank live, they just can't share that information with the neighbors.