|

Audio

Photos

Resources

|

|

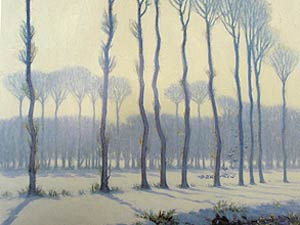

| Winter Mists (Winter Scene France), (ca. 1925 – 1935) Duluth-born David Ericson painted the same row of poplars painted earlier by Monet. (Photo courtesy Tweed Museum) |

Duluth, Minn. — It's a typically American story of a poor immigrant who achieved success. Born in Sweden, David Ericson immigrated with his family to Duluth. His parents were poor. As a child, he was confined to bed for three years because of an infection. A woman from a prominent Duluth family encouraged his interest in art. When he was 16, one of his paintings won a gold medal at the State Fair. Patrons in Duluth sent him to New York, and from there he went to Paris, where he studied with Whistler.

He sold his work in the big shows in Paris, New York, and Washington D.C. But he came back to Duluth time and again, to paint portraits and offer art classes. Newspaper photos show him in a suit, with a cigar.

Tom O'Sullivan is a curator and writer from St. Paul who wrote a chapter in a book produced about the exhibit. He says Ericson seems like a kindly uncle.

"Someone who had great stories to tell," O'Sullivan explains. "Someone who was clearly confident in the fact that he'd been right at the center and involved where some big things were happening." The big things in Ericson's life were the Impressionists, and James McNeill Whistler -- the American who is best known for his portrait of his mother -- but who was actually a pioneer in abstract art.

Ericson sold enough paintings to support himself and his family, through two world wars and the Great Depression. His success is documented in the lists of works shown in various galleries on both sides of the Atlantic.

"So you can look up Ericson at various times at something like the Corcoran Institute's annual exhibition in Washington," O'Sullivan says. "It's one of these things that becomes a benchmark historically for seeing, 'Gee, did this artist play in the big leagues, or were they just known in their home town?' and sure enough, year after year, you see Ericson's name."

Sometimes Ericson sent his work from Paris, sometimes from Provincetown, Massachusetts, and sometimes from Duluth. He moved easily between traditional, dignified portraiture and atmospheric, light-filled landscapes and water scapes.

Tweed Museum curator Peter Spooner says Ericson was an enthusiastic student of Whistler.

"Whistler was what I call 'Ericson's Modern,' his example of modernity," Spooner says. "Except for the fact that when Ericson connected with Whistler, Whistler was almost dead. He was in his last years. So Ericson's example of the Modern was already passe, by the time he connected with it." So Ericson's style was a generation behind the other artists of his age. And he didn't mind. He was aware of cubism and abstraction, movements that transformed the art world during his lifetime. But he stuck with what he knew: the tones of Whistler and the texture of Impressionism.

His studies of Venetian palaces bring to mind Monet's series exploring the Rouen Cathedral in different kinds of light. Ericson felt the shimmering palaces were his best paintings. And Spooner says they're a unique melding of Whistler and the Impressionists:

"Whistler, because of the tonal qualities -- the bluish cast and the tonal qualities that he's working with -- and Impressionism, because of the textural qualities that he's trying to achieve and paint," he says. "They have a thick, almost tapestry-like look to them."

Ericson's work is comfortable to look at. Pastoral scenes, plenty of light and texture.

Many of the paintings in the exhibit were loaned by Duluth families who have treasured them for a couple of generations.

But Spooner says there are more Ericson works out there.

"We believe that Ericson would have sold lot of work in Europe, and probably a lot of work in New York and Provincetown, where he also lived, that has not been located yet, so we think the story will continue," he says.

Spooner is creating an on-line catalog, which will include an easily-updatable list of Ericson's work, along with a biography and documents like letters and newspaper articles.

The exhibit continues at the Tweed Museum until January 15th.