Of the 12 races listed on the latest census form, only one has an official membership card. That document, known as "the white card," is what makes an Indian an Indian—at least in the eyes of many U.S. government and tribal programs.

Not surprisingly, the use of the white card to record a human pedigree raises civil rights concerns. The use of "blood quantum" to define a genetic cut-off point for Indian people is viewed by many as an instrument of assimilation or extermination. Yet over a century, blood quantum has become a deeply ingrained—and even valued—tool in the relations between sovereign tribes and the rest of world.

As a new generation of Indians comes of age, blood quantum reform may be closely tied to the future of Indian nations and cultures.

|

A discussion on the implications of blood quantum at the American Indian Center at St. Cloud State University. (Pictured, Rex Veeder, Director)

Launch RealSlideshow

|

COREY LAWRENCE IS A HALF-BLOOD SPEAR LAKE SIOUX. Lawrence, a junior at St. Cloud State University, is an enrolled member of the North Dakota tribe along with his father. But his mother is Ojibwe, and right now that means Corey Lawrence's grandchildren will probably no longer make the cut at Spear Lake.

"It's an iffy thing. I'm enrolled, but after my kids have kids that's it. They can't be enrolled any more and the funding stops. And that's what I think blood quantum was set up to do. In a way, it could be seen as genocide," says Lawrence.

The vast majority of Indian tribes require one-quarter blood, specifically from their reservation, for enrollment. One full-blooded grandparent, for example, would give someone a blood-quantum of one-quarter.

Today, blood quantum data is dispersed among the records of 558 federally-recognized tribes. But conventional wisdom holds that most enrolled Indians, especially in the younger generation, have a blood quantum of less than one-half. This is of some concern to groups like the Minnesota Chippewa.

"It's against our spiritual beliefs to marry someone within your clan," says Tom Andrus, who teaches Ojibwe history at St. Cloud State University. He notes the irony that Minnesota's Ojibwe clans can maintain their bloodline only by betraying their culture.

"Let's say I'm a quarter-blood from Fond du Lac, and I marry a quarter-blood from Mille Lacs. Our children are no longer considered Indian by the federal government, because they're not 25 percent from one nation," says Andrus.

And when you're not Indian enough, many tangible benefits stop. Generations within families can be divided by tribal enrollment. And Indian communities are torn between losing members through intermarriage, and the real or perceived role of blood quantum in keeping the remaining cultures pure and strong.

|

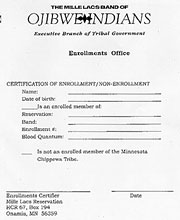

This is the enrollment certification form for the Mille Lacs band of Ojibwe, which asks for the holder's blood quantum.

(Image courtesy of Mille Lacs band)

View larger image

|

For this last reason, Andrus wouldn't do away with blood quantum. But he foresees more talk of reform as today's quarter-blood young people reach child-bearing age.

"I think that blood quantum is going to affect the basis of who we are, and it's going to affect it in a major way, in the next 15 to 20 years," says Andrus.

Blood quantum in the U.S. has been around longer than the country itself. In perhaps the earliest example, a 1705 Virginia colony law defines 'mulatto' to be anyone who was at least one-half Indian or one-eighth black. In Minnesota, the first appearance of the blood quantum may be the Treaty of 1837, in which one clause makes provisions for the "half-breed relations" of the Ojibwe.

The government came to adopt one-quarter blood quantum to distribute the resources tribes secured in treaties across the country. On one level, it was a bureaucratic necessity: Congress had to draw the line somewhere. The more cynical view assumes that the government had an outcome in mind.

"I don't think anybody then would have dreamed that we'd have lasted this long," says Andrus.

Indians are still around, and the blood quantum establishes the basis in most cases for tribal enrollment. With recent expansion of tribal sovereignty and innovation by reservation governments, being enrolled arguably matters as much as it ever has.

The Indian Child Welfare Act protects the cultural rights of enrolled children. Many Minnesota tribes will supplement state financial aid to meet the cost of a college education for tribal members. Tribal health services offer free or very affordable care for enrolled members. Some reservations, like Mille Lacs, can essentially guarantee members a job. And in rare cases, such as the Mystic Lake Casino owned and operated by the Mdewakaton Sioux, cash payments from tribal enterprises can make tribal members millionaires.

The Quandary of Blood Quantum

While both enrolled and non-enrolled Indians live on reservations, the much greater diversity within urban Indian communities can raise unique blood quantum issues. Read more.

|

A tribe's right to discriminate based on blood comes from its status as a sovereign nation. But blood quantum distinctions can divide families in a way that's unique.

Kathy Lawrence, a nursing student at SCSU, is more than one-quarter Ojibwe, but does not have enough Indian blood from either Red Lake or White Earth for tribal membership. Her half-brother does, but she worries there would be trouble if she joined him on family hunting trips.

"Up in Red Lake my brother hunts. They hunt and fish and snare rabbits, and do it as a family thing, learning about the land. I can't do that. That part's kind of hard because it's a family thing. I think that's the part I miss the most," says Lawrence.

No tribe or government service is obligated to use blood quantum. The White Earth Indian health center, administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, avoids tough choices by giving free health care to anyone who can show any relation to a recognized tribe.

"We want to take care of the whole family and extended family," says director Jon McArthur. "It could be really disruptive if certain members of the family were enrolled, and some were not enrolled. You could potentially provide services to maybe the parents and not the children. We want to provide services to all our people here," says McArthur.

|

Kathy Lawrence, a nursing student at St. Cloud State University, is more than one-quarter Ojibwe. But she doesn't have enough Indian blood from either Red Lake or White Earth to be a member of either tribe. She's concerned she'd get in trouble if she accompanied her half-brother, a Red Lake member, to hunt on the reservation.

(MPR Photo/Tim Post)

|

The White Earth clinic can afford this practice for now. But tribes - and many sympathetic non-enrolled Indians - worry that liberalizing enrollment on a large scale could put a major financial strain on Indian programs faced with increasing demand.

Some fear a cultural strain as well, if the blood quantum-based definition of "Indian" were to change. The new census figures will do little to allay such concerns. For the first time, the census allowed Americans to choose more than one race, and the number of people checking "Indian" doubled compared with 1990. It grew by 62 percent in Minnesota, to more than 81,000. But tribal records show actual enrollment may be closer to half that number.

The interim director of the American Indian Center at St. Cloud State, a descendent of the Choctaw nation, has light hair and blue eyes, and lacks the blood quantum for enrollment. But Rex Veeder understands the desire to protect the purity of tribal populations.

"Let's face it. Indian folks, rightfully so, are very nervous about people coming into their community, saying they're Indian, and kind of taking over stuff and appropriating the culture," says Veeder. "Personally, I like that. I kind of like the idea that people in certain communties keep that circle to themselves, and preserve their sovereignty and integrity as a people."

In coming years Minnesota tribes may look more closely to the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, which extends membership to anyone who can trace an ancestor to a 120-year-old membership list. The Cherokee add 1000 members each month, and are now arguably the largest tribe in the nation. They are also, perhaps, the most diluted.

The U.S. government decided more than 100 years ago that blood quantum was what made an Indian. But to many of today's younger native people, at least, it makes sense to look more than skin-deep -- at cultural values, religious practice, and whether they intend to contribute to the reservation community. Jenny Wharton, a 19-year-old freshman in St. Cloud, is Choctaw and Comanche.

"I personally don't know what my quantum is. I know it's about four generations back. But at the same time, I could be one one-hundredth, the smallest percent, and I'd still consider myself an Indian, because it's inside of me," says Wharton.

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that Minnesota's tribal elders are already one step ahead. In a move designed to address the issue of dwindling blood lines, the Minnesota Indian Council of Elders is asking state tribes to recognize one another's blood quantum as equally valid. As tribes ponder the proposal, another generation is coming of age.

Related Links:

Native American Heritage.com, a guide for Indian descendents considering tracing their roots and possibly enrolling.

Blood Quantum: A Relic Of Racism And Termination, an essay on the early history of blood quantum.

Challenge the Law of Genocide, an edition of American Comments web magazine that features a strongly-worded argument against blood quantum.

All Things Cherokee, a guide to resources around the web related to the Cherokee Nation.

A history of tribal enrollment from the American Indian Policy Center (located in St. Paul)

Minnesota's Indian Reservations, with a page dedicated to information on each.

Lyrics to the song Blood Quantum by the Indigo Girls.

|