By Mark Steil and Tim Post

Minnesota Public Radio

September 26, 2002

| |

|

|

|

||

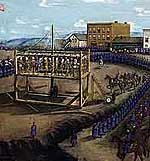

It was much harder for the Dakota to forget and forgive. Spurred on by public anger over the settler killings, the government hanged 38 Indians in late December. Most historians now believe the executions were based on flimsy evidence. They say innocent people were hanged.

In 1863, Congress threw out all treaties with the Dakota. Money promised the Indians instead paid the war claims of the settlers. All Dakota land was confiscated. And in the crowning blow, the Dakota were expelled from Minnesota. Those Indians who had fought, and those who had not, were treated the same. For good measure, the Winnebagos were also kicked out, even though they played no part in the hostilities.

"(The events of) 1862 are very real to us as Dakota people today," says Angela Cavendar Wilson, who teaches at Arizona State University. "The problems that we have in our contemporary communities are a direct consequence of losing our homeland, having attempts at cultural eradication perpetrated against us - and it needs to be addressed," Wilson says.

| |

|

|

|

||

The Dakota have been a divided nation since 1862, because white civilization split the Indians into factions. The government encouraged the Dakota to become farmers, Christians, students. Dakota traditionalists were angered by these "new" Indians - they might burn their crops, kill their livestock or worse.

John LaBatte has studied the war from all angles. His ancestors were Dakota and French. He says the Indian nation fractured under the weight of the war.

"Not all of the Dakota Indians started that war, and not all of the people who fought in the war committed the worst atrocities. Only a small group made all of the Indians look bad. A small number of that Dakota nation started the war and carried it on," LaBatte says.

Little Crow lead warriors into battle, but chiefs like Wabasha, Wacouta and Traveling Hail opposed war. Many of the chiefs said killing settlers was wrong, but LaBatte says they were ignored.

"Some of the Indians were forced into war by threat of death if they didn't join. Some of the Indians fled the area. Some of the Indians never were involved. They were out on the buffalo hunts, but they were blamed for the war," says LaBatte.

| |

|

|

|

||

When the fighting ended, Dakota turned against Dakota. Some volunteered to serve as scouts for the U.S. Army. Most did it to escape exile to one of the new reservations.

Ed Red Owl of Sisseton, S.D., says the scouts set up a screen of camps across North and South Dakota. Their job was to shoot any Indian returning to Minnesota. As many as 300 were killed. Red Owl says any scout disobeying the shoot-to-kill order was subject to military execution.

"One of the chief scouts here tells ... of encountering his own nephew. When he saw his nephew coming, he said, 'I had tears in my eyes, but yet I had the orders of the United States Army to fulfill. And so before my own eyes, I shot him until he died,'" Red Owl says.

After the war, the Dakota became a transient people. Their new home was wherever the government decided to send them.

|

"I did not hurt anyone, and now two of my younger brothers were hung and also two died a common death. I am the last of the brothers living because God had pity upon me."

- Letter written by Indian prisoner in Davenport, Iowa |

As one tribal Web site puts it, "The Indians were moved from state to state like a piece of unwanted baggage." First to Fort Snelling, then down the Mississippi River to Davenport, Iowa.

Letters written by the Indian prisoners at Davenport are just now being made public. The Flandreau Dakota are translating the letters. This one describes a disease-ridden prison camp.

"I'm going to tell you about something bad that I know. I grew up upon this earth, but now for six months we are suffering greatly. I am angry because of this and I am suffering much. If only God would give me strength. It is very cold, and I wish that it were summer. I think that as I am sitting here. I did not hurt anyone, and now two of my younger brothers were hung and also two died a common death. I am the last of the brothers living because God had pity upon me," the letter reads.

Disease and starvation followed the Indians to their next stop - Crow Creek, S.D. Some went south to Nebraska. Others wound up in northeast South Dakota, close to their old homeland. Some ended up in North Dakota and Canada.

More from MPR