Last Chance for the Higgins' Eye

By Mary Losure

July 14, 2000

Biologists on the upper Mississippi River are making a last ditch attempt to save a little-known endangered species: a small, mud-brown mussel known as the Higgins' Eye. Hoards of non-native zebra mussels infesting the Mississippi have devastated native mussel populations, and nearly wiped out the Higgins' Eye. Now, scientists are trying to evacuate the Higgins' Eye to tributaries of the upper Mississippi - places free of zebra mussels, where the native mussels can find refuge.

BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF ZEBRA MUSSELS, the Mississippi River at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin was one of the best places in the country to find native mussels. Kurt Welke used to scuba dive there when he first started working for the Wisconsin Department Natural Resources in 1988. The river bottom was clean sand and gravel, like a cobblestone path. Twelve years later, zebra mussels have made it unrecognizable.

"It would be like if I took about a million brown soda bottles and broke them into small pieces and spread them on the bottom of the river about six inches deep, that's what it feels like. It's very sharp, very angular, kind of crunchy. They do secrete a lot of slime, so it's a fetid environment," says Welke.

Zebra mussels hog food, space, and oxygen. They cluster so thickly on the native mussels' shells, they can't open.

Scientists who have dedicated their careers to native mussels have seen the number of species at their study sites plummet at an ever-accelerating pace.

Even before the invasion, Higgins' Eye mussels were rare. Now, they're almost gone.

So Welke and other biologists have begun raising them at a hatchery at Genoa, Wisconsin. They want to build up their numbers, then put them back in the wild.

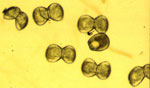

In their early stages, the mussels are so tiny, it takes a microscope to see them

"If you look long enough," says Welke, "you should see what looks like a little tongue sticking out. It's actually a foot."

In nature, tiny Higgins' Eyes find homes by hitching rides on fish. The mother mussel lures in a passing fish, using a special flap of skin that looks like a minnow. When the fish comes in close, the mother mussel sprays her young into its gills. The tiny mussels grow in the gills, then drop off and sink to the river bottom, where they reach maturity.

It's an ingenious, complicated life cycle. It was always a gamble, but the odds got worse when the Army Corps of Engineers built the lock-and-dams system on the upper Mississippi. The dams eliminated many of the fish the Higgins Eye and other native mussels depended on.

Now, Welke is trying, by artificial means, to improve the chances of the baby Higgins Eyes' survival.

On a bright summer day, Welke wades shoulder deep in the Wisconsin River, a few miles upstream of where it joins the Mississippi. He's looking for a suitable home for a batch of microscopic Higgins Eyes.

The Wisconsin here is a green and peaceful river, with a sand bottom free of zebra mussels. Welke searches for a spot where the currents are right, silt won't build up,and water levels are sufficient. "In this river, you can lose a foot of water overnight," he says. That would give us three. I'd feel better if we were in five."

Welke finds what he hopes will be a good spot. He and his assistant line shallow, wooden trays with gravel, then add muddy sand from the river bottom. They put a screen on the top of the trays, to keep out predators. Just before they sink them to the river bottom, they pour in a few cups of what looks like sandy water - thousands of microscopic mussels voyaging into new territory.

If all goes well, a couple-hundred young mussels will make it in these boxes.

Higgins Eyes can live as long as 40 years. Welke hopes if they can just hang on in Mississippi tributaries like the Wisconsin, someday conditions will improve on the Mississippi itself, and the mussels can be saved from extinction. It's a long shot, but he's devoted a good part of his life to it.

"Why is this so important? It's an aesthetic consideration. These animals have been here since the dawn of time. They should be here, they deserve to be here. I obviously have a bias; I have a fondness towards them, it just seems incumbent that we do something so that they just don't cease to exist here. It's important. I can't give you an economic role that they provide, I can't give you a cure cancer justification, but they're here, and they've always been here, and that's good enough for me."

For years, biologists like Welke were the only ones who paid much attention to the plight of the Higgins Eye, but recently the mussel got a new ally: the U.S Army Corps of Engineers.

In May, the Federal Fish and Wildlife Service declared that the Corps of Engineers' navigation operations on the upper Mississippi jeopardize the Higgins' Eye's survival. The Corps must begin a program like the one Welke and his colleagues pioneered, relocating mussels onto Mississippi tributaries. Suddenly, a powerful agency has a lot riding on the fate of a small, mud brown mussel. Its long odds for survival may be looking up.

By Mary Losure

July 14, 2000

|

|

RealAudio 3.0 |

Biologists on the upper Mississippi River are making a last ditch attempt to save a little-known endangered species: a small, mud-brown mussel known as the Higgins' Eye. Hoards of non-native zebra mussels infesting the Mississippi have devastated native mussel populations, and nearly wiped out the Higgins' Eye. Now, scientists are trying to evacuate the Higgins' Eye to tributaries of the upper Mississippi - places free of zebra mussels, where the native mussels can find refuge.

| |

|

|

|

||

BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF ZEBRA MUSSELS, the Mississippi River at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin was one of the best places in the country to find native mussels. Kurt Welke used to scuba dive there when he first started working for the Wisconsin Department Natural Resources in 1988. The river bottom was clean sand and gravel, like a cobblestone path. Twelve years later, zebra mussels have made it unrecognizable.

"It would be like if I took about a million brown soda bottles and broke them into small pieces and spread them on the bottom of the river about six inches deep, that's what it feels like. It's very sharp, very angular, kind of crunchy. They do secrete a lot of slime, so it's a fetid environment," says Welke.

Zebra mussels hog food, space, and oxygen. They cluster so thickly on the native mussels' shells, they can't open.

Scientists who have dedicated their careers to native mussels have seen the number of species at their study sites plummet at an ever-accelerating pace.

Even before the invasion, Higgins' Eye mussels were rare. Now, they're almost gone.

So Welke and other biologists have begun raising them at a hatchery at Genoa, Wisconsin. They want to build up their numbers, then put them back in the wild.

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

In nature, tiny Higgins' Eyes find homes by hitching rides on fish. The mother mussel lures in a passing fish, using a special flap of skin that looks like a minnow. When the fish comes in close, the mother mussel sprays her young into its gills. The tiny mussels grow in the gills, then drop off and sink to the river bottom, where they reach maturity.

It's an ingenious, complicated life cycle. It was always a gamble, but the odds got worse when the Army Corps of Engineers built the lock-and-dams system on the upper Mississippi. The dams eliminated many of the fish the Higgins Eye and other native mussels depended on.

Now, Welke is trying, by artificial means, to improve the chances of the baby Higgins Eyes' survival.

On a bright summer day, Welke wades shoulder deep in the Wisconsin River, a few miles upstream of where it joins the Mississippi. He's looking for a suitable home for a batch of microscopic Higgins Eyes.

The Wisconsin here is a green and peaceful river, with a sand bottom free of zebra mussels. Welke searches for a spot where the currents are right, silt won't build up,and water levels are sufficient. "In this river, you can lose a foot of water overnight," he says. That would give us three. I'd feel better if we were in five."

Welke finds what he hopes will be a good spot. He and his assistant line shallow, wooden trays with gravel, then add muddy sand from the river bottom. They put a screen on the top of the trays, to keep out predators. Just before they sink them to the river bottom, they pour in a few cups of what looks like sandy water - thousands of microscopic mussels voyaging into new territory.

| |

|

|

|

||

Higgins Eyes can live as long as 40 years. Welke hopes if they can just hang on in Mississippi tributaries like the Wisconsin, someday conditions will improve on the Mississippi itself, and the mussels can be saved from extinction. It's a long shot, but he's devoted a good part of his life to it.

"Why is this so important? It's an aesthetic consideration. These animals have been here since the dawn of time. They should be here, they deserve to be here. I obviously have a bias; I have a fondness towards them, it just seems incumbent that we do something so that they just don't cease to exist here. It's important. I can't give you an economic role that they provide, I can't give you a cure cancer justification, but they're here, and they've always been here, and that's good enough for me."

| |

|

|

|

||

In May, the Federal Fish and Wildlife Service declared that the Corps of Engineers' navigation operations on the upper Mississippi jeopardize the Higgins' Eye's survival. The Corps must begin a program like the one Welke and his colleagues pioneered, relocating mussels onto Mississippi tributaries. Suddenly, a powerful agency has a lot riding on the fate of a small, mud brown mussel. Its long odds for survival may be looking up.

| Next: Small Victories |