The Wireless Tether

By Andrew Haeg, Minnesota Public Radio

March, 2001

|

|

RealAudio |

Wireless technologies are changing the way Minnesotans live, and nowhere is the potential impact so clear as on the job. New technologies are allowing workers to roam without losing touch. The pay-off for employers is clear: more efficient staff, lower costs, and - in some cases - better customer service. But some workers wonder if they've been liberated, or bound ever more tightly to the office.

| |

|

|

|

||

Northwest agent Pari Mukadam checks in Chicago-bound passenger Dave Berg. Mukadem's wearing what looks like a fanny pack around her waist, a little printer on her hip, and she's holding a tablet-sized computer screen in her hand. It's a wearable computer, made by a Minnesota company named Via. It's got all the functions of the computers behind the counter, without the wires.

She uses a stylus to tap in the information, which her computer sends to the front office via radio frequencies. The little printer on her hip spits out a boarding pass and Berg is on his way, without ever waiting in line.

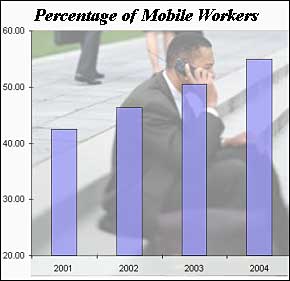

There are roughly 40 million mobile workers in America, according to IDC, a research company based in Massachusetts. They range from those like Mukadem who just need to walk around, to more peripatetic souls like truck drivers, salespeople and even financial analysts who need to spend much of their time away from the office. Many companies have been using Internet-based techniques to cut out middlemen and streamline operations for the past two or three years. But the latest tech wave is just now gathering speed.

Andy Seybold runs a wireless communications consulting service in California, and writes a column on wireless technologies for Forbes Magazine. He says most businesses aren't yet using wireless data devices; his estimates suggest only about a million Americans use things like Internet-ready palm-top computers. But, increasingly, Seybold says companies across the economy are turning to wireless technology for two reasons.

"First of all, you gain a competitive edge," he says. "And the second thing is that you can do more with the same number of of people. It's not about reducing your fleet of people by 10 percent or something, but it's about being able to take the same number of feet on the street and actually get more productivity out of the whole group."

For now, those companies embracing wireless technology are mostly those competing for customers based on the quality of the service they provide.

Truckdriver Bill Hackett used to leave home base knowing he'd be out of touch until he could get to a phone. Hackett delivers meats for J& B Wholesaling, based in St. Michael. As he delivered a load of beef to Von Hanson's meats in Savage, he has a Palm Pilot mounted on his console, and a small, global-positioning unit suctioned to his dash.

He reaches Von Hanson's, and taps a message to his dispatcher into his Palm Pilot. Hackett informs the dispatcher he's dropped off his load. That means J & B can issue a bill right away. The home office already knew where he was. The tracking system J& B uses is called e-trace, developed by Minneapolis-based Gearworks.

With e-trace, J& B's dispatcher can follow Hackett and his colleagues live on a map and e-mail them with new stops or other information. And Hackett can receive road condition reports to avoid bottlenecks, and exchange e-mails with his family.

Kurt Anderson is J& B's director of operations, and a self-described technophile. He's a big reason J& B's warehouse employees track inventory with wireless devices; and why all of J& B's 72 semis will soon have Palm Pilots like Hackett's in their cabs. Anderson says wireless technology gives J& B an edge in the competitive meat delivery industry.

"A box of beef is a box of beef when you go to buy it," he says. "And there's quality issues, and we sell the best quality we can. But the other thing we find to this is that we need to sell service. And with this we're offering a service that very few people are able to offer."

For J & B, new technologies are improving customer service, its clients can keep track of their shipments if the meat hasn't arrived on time, they'll know where it is and why it's late.

New technologies are helping workers in many other businesses do more with their time. George Dahlman is a senior analyst for US Bancorp Piper Jaffray. He follows several food and ag companies for Piper investors, and he's addicted to his personal digital assistant, or PDA. With his so-called Blackberry, he can send and receive e-mail anywhere, surf the Internet - albeit slowly - and he can find maps and write notes. When e-mails come in, it vibrates.

One evening Dahlman was on his way to his son's ninth-grade basketball game when his PDA rattled in his shirt pocket. ConAgra was announcing an earnings shortfall, but Dahlman had committed to keeping score for the basketball game. Throughout the game, Dahlman received a stream of e-mails from his associate.

During timeouts and half time, I was looking at my Blackberry reading those and responding back to him. As soon as the game was over I summarized the scoring, gave the book to the coach, told my wife I was going back downtown. Meanwhile, I talked with my associate by telephone on my way back down from Blaine, got in here and figured out what we needed to do for the next day," Dahlman said.

Access to wireless technology let Dahlman keep a promise to his son. But at the same time, he agrees, his precious Blackberry is a sign that his job is claiming a greater part of his life.

"It's a recognition that this is an around-the-clock type of a job. But at the same time it means that we're not necessarily tied to being in the office to get it done. That we can respond to questions from our associates whether or not we're sitting at a basketball game, sitting in an airport waiting for an airplane, or at our desk," he says.

Being "always on" has other implications. There are some who say wireless technologies are tools of Big Brother, tracking our every move. Though his employer knows where he is at all times, truckdriver Bill Hackett doesn't feel oppressed.

"It's getting to be part of the business now. It's their equipment, it's their money. They can keep better track of time which allows me more time with my family now," he says.

All in all, most agree the benefits of wireless devices outweigh the costs. Andy Seybold says it's hard to precisely measure those benefits. But he agrees that as anecdotal evidence flows in from companies like J & B, Piper Jaffray and Northwest, more technology managers will be able to offer their bosses compelling reasons to put a wireless device in the hands, and around the waists, of their most mobile workers.

Cutting the Cord | Wireless' Lab Rats | The Wireless Tether | Rural Minnesota's Place in the Wireless Derby | A Delicate Balance | Home