Racial Disparities - An Overview

By Dan Olson

Minnesota Public Radio

November, 2001

|

| RealAudio |

An overview | Accountability in the justice system | American Indians and the rural justice system | The new disparities | Driving while black

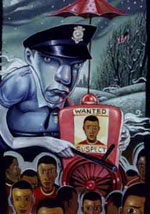

Racial profiling, many white Minnesotan's believe, does not happen here. Lawmakers have declined to authorize collecting numbers on the practice, and some of the state's top law enforcement officials say it's not a problem. However, the numbers tell a different story. Analysis of police stops in Minneapolis and St. Paul shows black men are stopped at a rate far greater than their presence in the population. Once in the criminal justice system, black men in Minnesota are prosecuted, convicted and sentenced at a higher rate than whites. Anecdotes and evidence from other parts of the state hint at a similar pattern for blacks and American Indians.

| |

|

|

|

||

The blizzard of statistics numbs the brain, and the point is difficult to grasp until Tom Johnson pulls a breathtaking number from the pile on his desk.

"We know, for example, that in 1999 in Hennepin County you had over half of all African American males between 18 and 30 arrested in that one year," says Johnson, who was Hennepin County attorney in the 1980s.

Now he's president of the Minneapolis-based nonprofit Council on Crime and Justice, the group putting together a new analysis of racial profiling for the Minneapolis police department.

The reaction of some who believe black men commit most of the crime is the black arrest rate makes sense. Tom Johnson says the numbers don't support the presumption.

"To use who is arrested as gauge to make decision about who is committing crime isn't accurate or fair," he says.

Others say the high black arrest rate can be explained by racial profiling - police stopping black men for no other reason than the color of their skin - in the Twin Cities and elsewhere. Ray Jefferson says his wife saw the sheriff's deputy whip his cruiser around and start following them. "My wife had made the comment, 'Well I think he's going to pull us over.' And I assured her there was no reason that he would do that," Jefferson recalls (Listen to an extended interview with Ray Jefferson).

Ray Jefferson and his family were on a fishing vacation last summer at a northern Minnesota resort. They had finished buying groceries in a nearby town. They turned onto the highway to head back to the lake when they were pulled over. The sheriff's deputy stopped them because Jefferson wasn't wearing a seat belt.

"He then was kind of taken aback at that moment once I told him that I knew that that was not a stoppable offense, and that I knew that because I was an officer too," he says.

There've been attempts to make not wearing a seat belt a stoppable offense, but lawmakers haven't approved it. Jefferson says the deputy then told him he'd pulled them over for another reason, "and that was because I had a ribbon hanging from my rear view mirror," he says.

Items hanging from a review mirror are considered a distraction to driving; Minnesota law prohibits them and police can - but seldom do - stop drivers because of it.

| |

|

|

|

||

Jefferson says after checking his identification, the deputy returned to the car and said he wouldn't issue a ticket this time.

St. Paul Police Sgt. Ray Jefferson, a 10-year veteran of the force, a middle-aged father of four, declines to talk about the many other times he's been stopped for no apparent reason other than the color of his skin both in the Twin Cities and outstate Minnesota. He recounts this summer's episode with reluctance.

As a police officer, he knows there are often good reasons - erratic driving, people who match the description of a suspect - for police to stop them. But he also knows from experience that there are times when black men are pulled over because of their race.

"When I take my badge and gun and hang it in the closet when I'm off duty, I expect to be treated in a certain way, just like any other person would expect to be treated regardless of the color of their skin," Jefferson says.

The numbers show black men are treated differently.

During six months last year, Minneapolis police stopped black drivers at a rate more than twice their numbers in the population. An analysis of St. Paul police stops shows a similar ratio. Earlier studies show that once in the Hennepin County criminal justice system, blacks are more likely to be charged with drug crimes. When blacks and whites are charged and convicted of similar crimes, blacks are more likely to serve time behind bars.

The result is the ratio of blacks sent to Minnesota prisons compared to whites is the highest in the country.

However, there's no evidence to show blacks are more crime prone than whites, and no evidence showing they use drugs more frequently. In fact the evidence shows whites and blacks use illicit drugs at about the same rate.

Is racial profiling - blacks stopped by police for no other reason than the color of their skin - the sole reason they are disproportionately represented in Minnesota's criminal justice system? Minneapolis police Lt. Isaac Delugo doesn't deny racial profiling happens. But he says it doesn't cause the disparity.

| |

|

|

|

||

Lt. Delugo is in charge of training for Minneapolis police. He says police respond to calls, many from the city's poorest neighborhoods where a lot of the residents are black.

"When they get complaints from the citizens of that neighborhood, who I might add the victims are people of color, they demand that you do something about a crack house on a corner, they demand that you do something about the four or five young men on the street corner who they presume are selling drugs and they possibly are," says Delugo.

In Minneapolis and many other large cities, police target their resources at neighborhoods which generate lots of police calls. Lt. Delugo says stopping people in those neighborhoods for relatively minor infractions - jaywalking, loitering, broken tail lights - often stops criminals in their tracks. "It is through those stops -those officer contacts - that police do find the drugs, the guns, the felony warrants for murder, that type of thing," he says.

The strategy, many agree, works. The crime rate is down. That the jail cells and courtrooms are filled with black people supplies all the evidence many need to arrive at the conclusion black men commit most of the crime. Thus, targeting a population is good police work.

"It turns out that that isn't so," says David Harris, who adds that race is a poor indicator of who commits crime. He's a University of Toledo law school professor who is one of the country's most outspoken critics of racial profiling.

Harris says his and others' analysis of police records in cities where blacks are stopped and searched more often than whites leads to a disquieting finding: Racial profiling does not lead to catching more criminals.

|

"Let me have you pulled over for the next six nights 'til you get the idea this might be happening because of the color of your skin and see if you don't put a foot in the side of that squad car."

- Tom Johnson, Council on Crime and Justice |

"When we use profiling to focus on who we should stop and who we should question and who we should search, the results of our police efforts are actually lower, our police are actually less effective than when they use such traditional methods of observing behavior, using intelligence and so forth," Harris says.

A response to Harris' view is most of the calls for police help come from poor neighborhoods. People living there who are stopped by police, but have committed no crime, have nothing to fear.

"And we may say to them, 'Well, it's not such a big deal; you should just put up with it.' But the hurt, the humiliation, the anger does not go away when they know their skin is what is getting them picked up. No driver is perfect and if we don't treat all drivers the same without regard to skin color, we'll have an infection in our body politic and it's going to hurt a lot of our institutions that we have, trust in the rule of law, it's all on the line with this issue," Harris says.

Trust in the rule of law takes another hit once blacks enter the criminal justice system. People who are black account for 70 percent of Hennepin County's drug cases. If convicted, they are sentenced to time behind bars at three times the rate of whites guilty of the same offense.

Racial disparity, some argue, is built into Minnesota's legal system. Consider the consequences for drunk driving. Most of the people charged with driving under the influence, Hennepin County Attorney Amy Klobuchar says, are white.

| |

|

|

|

||

"You go to the workhouse, you may do some treatment, pay some fines. That's it. You can have 23 DWI's and not have a felony and not go to prison. Whereas if you are arrested with even a small amount of drugs, you will have a felony on your record, so that creates a disparity at how we look at two different racial groups," according to Klobuchar.

There's been progress in reducing racial disparity in Minnesota's criminal justice system. The situation was much worse 11 years ago. That's when Legal Aid attorneys called to Hennepin County Judge Pamela Alexander's attention the punishment for people using crack cocaine compared to those using powder cocaine.

In the rush to advance the war on drugs, Minnesota lawmakers had approved mandatory prison sentences of four years for users of crack, a derivative of cocaine that's cheap and common on inner-city streets. Powdered cocaine, on the other hand, is seen by some as the suburban alternative - more popular among whites. State law prescribed probation for powder cocaine users.

Judge Alexander ruled - and the Minnesota Supreme Court agreed - that the disparate penalties were unconstitutional.

"The penalties were then equalized in the state of Minnesota. Hasn't been done anywhere else, but here in Minnesota we'll do it fairly," Alexander says.

Alexander was on the 1993 Minnesota Supreme Court Racial Bias Task Force. The group found the criminal justice system is rife with inequity based on skin color. Some blacks arrested on a Friday were jailed up to three days in Hennepin County only to have charges dismissed. The high dismissal rate suggested many were arrested on flimsy charges. A judge now comes in Saturdays and Sundays to review cases.

| |

|

|

|

||

The task force found that juries were nearly all white. The search for jurors was expanded, day care and transportation were offered. The jury pool these days is more diverse.

Judges were accused of racially insensitive remarks. Training for judges and court staff was begun and court watchers monitor behavior.

Problems remain - alongside claims that racial profiling is not a problem in Minnesota. Numbers continue to show a disproportionate number of blacks are stopped, arrested, charged, convicted and imprisoned.

Council on Crime and Justice Executive Director Tom Johnson, slight and soft spoken, laughs ruefully at the observation that white Minnesotans are bored with the issue of racial profiling.

"To say that this might be something that is less than important or boring, it blows me apart. My Scandinavian juices have a hard time not wanting to find this person and say 'you're wrong. Let me have you pulled over for the next six nights 'til you get the idea this might be happening because of the color of your skin and see if you don't put a foot in the side of that squad car,'" Johnson says.

The numbers collected by Tom Johnson's Council on Crime and Justice, along with those being collected by courts in each of Minnesota's counties, will be used by lawmakers and others to see how far the state has come in its treatment of people of color in the criminal justice system and how much more work remains to be done.

More Information