By Brandt Williams

Minnesota Public Radio

February 4, 2002

|

| RealAudio |

When Africans immigrate to America, they confront racism, perhaps for the first time. The longer they live in this country and become African-Americans, they realize they are identified more by the color of their skin than by their nationality. Race can complicate the process of assimilation for African immigrants.

| |

|

|

|

||

Daniel Abebe is a professor at Metro State University in St. Paul. He says the American concept of race may be hard for African immigrants to grasp. Abebe says that's because no matter where in Africa you're from, in America, you're black.

"When someone just simply reduces you to 'you are black,' for Africans, that's a very difficult concept to welcome," says Abebe. "I had that difficulty earlier on. I kept saying 'I'm not, I am an Ethiopian, I have a culture. I have a language. What do you mean I'm just that?'"

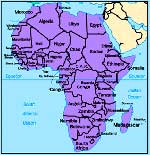

Abebe came to the U.S. to study in 1967, went back to Ethiopia and then returned to the U.S. in 1990. He says when Africans were first brought to U.S. shores as slaves in 1619, they identified themselves by tribe or nation.

They were Yoruba, Ibo, Akan and Ashanti. Abebe says America sought to control the captive Africans by stripping them of their culture and language. And he says some African immigrants resist the label 'black,' because they see it as an attempt to rob them of what makes them unique.

Abebe says as time passed he has learned to accept this part of American culture. And so have other African immigrants.

"I have begun to identify myself as an African-American," says Kenneth Udoibok, who was born in Nigeria and came to the U.S. 21 years ago.

He says the process of becoming an African American has been gradual.

"Ten years ago I told people I was an African. Fifteen to 20 years ago I told people I was a Nigerian," he says.

Udoibok says although he identifies himself as an African-American, racism in America is still difficult to wrap his African mind around.

| |

|

|

|

||

In Nigeria there are three major ethnic groups - the Yoruba, the Ibo and the Hausa. Udoibok is from the Ibibio, a subgroup of the Ibo. But he says he mostly lived around the Yoruba people.

Udoibok says there may be tension among the groups, even sporadic fighting. But he says that tribal tension is a far cry from white America's historic treatment of African Americans.

"The Hausa does not view Ibo as subhuman or inferior, neither does no tribe view the other as inferior," says Udoibok. "There's never been a law in Nigeria that portends to address one group as inferior to the rest of the groups."

Udoibok says dealing with racism in America has been physically and mentally taxing. He says only half-jokingly African-Americans should take time on a regular basis to see a psychologist. Udoibok says he hopes to eventually move back to Nigeria to continue his law practice and live out the rest of his days.

But some African immigrants don't see themselves returning home anytime soon, certainly not refugees from Sudan.

In Sudan, civil war between the north and the south has raged for many years. The north is dominated by Arabs and Muslims. In the south are Christians and followers of traditional religions.

| |

|

|

|

||

Most of the Sudanese in Minnesota are from the southern part of the country, where they say their people are being forced to speak Arabic and follow Islam.

"By coming to America, it was my first time...to know that people are discriminated because of their color," says Ruey Dong, a Sudanese refugee. "Back home, we don't have that kind of discrimination."

Dong is one of several hundred Sudanese refugees who moved to Minnesota - he's been here since 1994. Dong is a member of a group based in Columbia Heights, which tries to help other Sudanese refugees adjust to life in America and Minnesota.

Dong sits with two other Sudanese men in a wood-paneled room in the organization's headquarters.

"We feel like black Americans feel. Like we are treated differently by white Americans," says Dong. "For example, you can be stopped on the street by police while you are driving - while you didn't do anything."

Dong says his group is trying to connect with African-American organizations. He says they look to African-Americans as allies in the fight against racism.

Thomas Riek came from Sudan in 1995. He says there's another important reason for African-Americans to help the Sudanese.

| |

|

|

|

||

"Sooner or later after 20 years those kids, Sudanese kids, will not be called Sudanese kid anymore. They will be African-American," says Riek.

But to some Africans, that's not necessarily a good thing.

"If you heard my daughter talking, she doesn't talk like me. She got no accent, she's more or less African-American or American," says Jackson George, who came to the U.S. from civil war-torn Liberia in 1995.

Since 1980, the west African nation has undergone periods of war, instability and rebuilding.

George says he's interested in preparing his family and other Liberians for the day when they can return home, and do their part to put the pieces back together. However, he says time is running out.

"That is our fear, because our time is passing. I might not go back to Liberia, I might not even try to do it," says George. "But what about my daughter, who maybe after 20 years from now, there might be peace. Will she want to go back home? No. She doesn't know anything about it."

Daniel Abebe says young African immigrants are particularly apt to adopt African-American culture. He says young Africans can identify with black culture because in many ways it is very similiar to their own.

Abebe says process of turning Africans into African-Americans is beneficial to each group.

"I think it's going in the direction that it should - the alliances between these communities - because I think ultimately they are going to become one," says Abebe. "Because society's going to force them to be one. Their issues are going to be similar. Their struggles are going to be similar. And ultimately, I think their successes are going to be shared."

Abebe says like other new arrivals to America, African immigrants have mostly migrated to urban areas.

He says there, African immigrants often come into contact with African-Americans, thus accelerating the assimilation process.

More from MPRMore Information