By Brandt Williams

Minnesota Public Radio

February 4, 2002

|

| RealAudio |

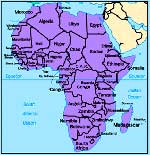

Minnesota has always been a destination for African immigrants. Their numbers have greatly increased since 1990 when refugees from Somalia, Sudan and Liberia arrived here to escape civil wars in their home countries. The African presence offers both a positive and perplexing situation for the state's African-American population. On one hand, by interacting with continental Africans, African-Americans make connections which help them better understand their cultural heritage. At the same time, these interactions sometimes serve to remind African-Americans of how far removed they are from Africa.

| |

|

|

|

||

"'Two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings in one dark body.' Boy, that's a great description he gave."

Macalester College history professor Mahmoud El-Kati ruminates on a passage from W.E.B. Dubois' seminal work, The Souls of Black Folk.

"'Whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.' That's who black people are. We're like two people."

In this often-quoted piece, DuBois described the identity crisis of black Americans. Unlike other immigrant ethnic groups who became hyphenated Americans and then just Americans, blacks were forced to come here and forced to leave their heritage behind.

But once freed from slavery, blacks drifted in cultural limbo. They were too far removed from Africa to go back, and faced resistance from whites as they strived to participate in American society as citizens.

They were, in a sense, not quite Africans and not quite Americans. Numerous movements throughout history have sought to connect black Americans with their ancestral roots. The term "African-American" emerged from those movements.

Malcolm X used the term "African-Americans" in a speech called the "Ballot or the Bullet" in 1964. In the speech, he said blacks are Africans living in America.

But how African are African-Americans?

"African Americans are pretty much Americans," says Alfred Babington-Johnson. You could say he is a true African-American. He was born in Nigeria but raised in America.

His mother is an African-American, while his father is from the Yoruba people of Nigeria.

| |

|

|

|

||

Babington says from his perspective, much of America's prejudices about Africa have rubbed off on African-Americans.

"Tarzan had an impact on African Americans," says Babington. "Strangely enough, I think there was a period of time when African-Americans watching Tarzan probably identified more with Tarzan than the people he was interacting with - who were indigenous to Africa."

Babington is the CEO of the Stairstep Initiative. The group helps fund black entrepreneurs in the Twin Cities. For the past several years, Stairstep has taken African-Americans to Ghana, West Africa.

Babington says some African-Americans who have made the trip brought some of those American stereotypes of Africa with them. He says some expected to see lions, or were disappointed to see modern cities.

However, Babington says nearly all the African-Americans who make the journey felt a sense of connection with their heritage.

He says even without going to Africa, African-Americans can recognize they have an inner African voice that challenges the American urge toward individualism.

"I think there is this counter surge within us - within most of us to one degree or another - that is more familial, that is more communal, that has a sense of, 'Isn't this our community? Can't we move together?' And I think those two impulses, in many ways, are at war with one another," says Babington.

"African-Americans are more African than many people realize," says Kenneth Udoibok. He came to the U.S. from Lagos, Nigeria 20 years ago. He works as an attorney in St. Paul and is married with two children.

Udoibok says he realizes that African-Americans have adopted many American values. However, he says he's amazed at how African-Americans have maintained many aspects of African culture.

| |

|

|

|

||

Like Africans, He says African-Americans have a strong love for religion, family, music and dance. But Udoibok says black American music is the strongest link to Africa.

"If you take rap for example, or R & B, and you compare the beat with the drums of the Yoruba or the Ibo people - it is very very similar, it is almost scary," says Udoibok. "To see these are people who have not had contact with each other for so many years. But the culture has survived such abuse."

Participating in African-rooted rituals and ceremonies, like Kwanzaa, is one way African-Americans nurture their African side.

In December, more than 1,000 people came to the State Theater in Minneapolis to watch school children perform tributes to African culture with drumming, singing and dancing.

Titilayo Bediako was born and raised in Minnesota, and is the daughter of civil rights leader Matthew Little. She was instrumental in putting together last year's Kwanzaa celebration.

Bediako says participating in African rituals helps give African-American youth a sense that they belong to something larger than themselves or their surroundings.

She says that's something she never received when she was in school. After graduating from high school, she moved to Tennessee where she joined an African history study group.

"The more I studied and the more I learned about myself, the more my given name, which was Michelle Little, didn't fit the person I had become," says Bediako.

The name Titilayo is from the Yoruba of Nigeria. She says it means "everlasting happiness." Bediako is from the Ashanti people of Ghana and it means, "born to struggle for her people."

| |

|

|

|

||

"So I get everlasting happiness in struggling for my people," says Bediako. "The one thing that I've learned is that struggling for African people makes it possible to struggle for all people."

Like Bediako, many African-Americans have adopted African names. However, despite attempts to identify with Africans, African-Americans carry the physical and emotional baggage of slavery and racism.

Bediako says many African-Americans have poor self-esteem because they were born in a country that historically has devalued their lives.

African immigrants haven't been exposed to American racism in the same way as African-Americans. But many have experienced the horrors of war and poverty. Bediako says despite that, African immigrants and refugees arrive in Minnesota with their self-pride intact.

"I think that's one of the greatest lessons that brothers and sisters can teach us that come from the continent - that we are a great people and no one can take it away from them," says Bediako.

In Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. DuBois wrote that the American Negro longs to merge his blackness, or his African self, with his American identity without losing either side.

He believed that both cultures have much to teach the world. At the time of its publication in the early 1900s, blacks were referred to as Negroes. DuBois would probably have preferred the phrase, African-American.

More from MPRMore Information