Part 5: Where tradition thrives

August 20, 2003

|

| Ponemah means "a little later," or "hereafter." Some say it's the most traditional Indian community in Minnesota, and perhaps the country. (MPR Photo/Tom Robertson) |

Ponemah, Minn. — For those who practice spiritual rituals, the heart of the Red Lake Reservation is the town of Ponemah. Christianity flourished in many reservation communities. But it never gained a large following in Ponemah.

The town is isolated from the more populated areas of the reservation. It sits on the shore of lower Red Lake, surrounded by pine forests. About 1,000 people live here, many in rundown government-built homes. Some of the homes have traditional family burial plots right in their front yards. The people here have closely guarded their traditional ways.

At the public elementary school, young boys are taught early about the importance of the drum. They proudly and passionately sing ancient songs.

| |||

Ponemah means "a little later," or "hereafter." Some say it's the most traditional Indian community in Minnesota, and perhaps the country. The people here are clannish. There's less intermarriage with outsiders. Nearly everyone follows traditional spiritual ways.

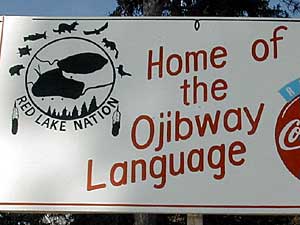

Visitors to Ponemah are greeted by a sign that says "Home of the Ojibwe Language." But even in Ponemah, the language is fading. Wesley Cloud grew up in Ponemah and was in the youth drum group. He's now custodian at the school and teaches drumming to the boys. Cloud guesses maybe one in 10 school kids can speak fluent Ojibwe. That makes it hard to maintain spiritual traditions.

"That's the way our elders are to greet the Great Spirit, in their Ojibwe language. People that don't understand language, it's probably difficult for them to, you know, make a prayer to the Great Spirit, because our Great Spirit is Anishinaabe," says Cloud.

Christian churches have tried for years to get a foothold in Ponemah. There's a small Christian church in town, but not many people go. Orianna Kingbird, cultural director at Ponemah Elementary School, says some Christian pastors used trickery to convert Indians.

| |||

"Our reverend that was back here in the '70s, he was baptizing all the young kids," Kingbird says. "And that was not our way. I had to be one of those kids that got loaded on a bus that thought they were going swimming, but ended up going to be baptized."

Ponemah's resistance to outside influences has created divisions on the reservation. Some Christian Indians view Ponemah as a backwards town. Kingbird says there's a stigma to growing up traditional.

"I know through all the years, that when kids have left from Ponemah to go to Red Lake, we were called savages. We were called heathens, you know, because of our way. We kept our way," Kingbird says. "I don't want to blame the church or blame the Catholics, for anything like that. It's just, when you're taught something, that's what you know."

Learning about spirits begins at an early age. Kids as young as 10 are sent into the woods alone for several days on a spiritual quest, where they fast and pray. Tony Treuer, an Ojibwe language professor at Bemidji State University, says those on the quest ask the spirits for a dream to guide them. The dreams can be life changing.

| |||

"The spirits might gift someone with a medicine, they might gift someone with a song. They might gift someone with, you know, the right to give names, and give them a whole bunch of Indian names to give to different people," says Treuer. "There might be all kinds of different ways a person could be gifted. And sometimes just one remarkable gift, you know, is enough for someone to be seen as a real spiritual leader. And to be a real spiritual leader."

There are typically only a handful of spiritual leaders within a tribe. Spiritual leaders provide advice and guidance to those who ask. They pray to the Great Spirit on behalf of the community. They perform traditional burial rites. They also run Midewiwin lodges.

Midewiwin is sometimes called the Grand Medicine Society. The initiation ceremony is usually conducted from spring through fall. Hundreds of people go through the ceremony at Midewiwin lodges across Minnesota each year. Most traditional people go through it sometime in their lives. The initiation signifies committing one's soul to walking a spiritual path.

The Midewiwin lodge in Ponemah sites in a small clearing in the woods. Rough ironwood timbers make a framework about 50 feet long. The rounded top is left uncovered when the weather is good. A tarp is thrown on when it rains.

People come to the Midewiwin lodge in Ponemah from throughout the Midwest and Canada. They come for healing and instruction. The complex, two-day initiation ceremony is conducted in Ojibwe. Leaders use birchbark scrolls to help them recall the ceremony. Ojibwe language professor Tony Treuer says symbols etched in the bark are used to trigger memories of songs and stories.

| |||

"It's a really elaborate ceremony, a legend that can take anywhere from two to six hours to tell. And if you miss a detail, it's a big no-no," says Treuer. "So even for fluent speakers, learning the details of this elaborate ceremony is tough. And so as a result, there's just a small handful of people that can run a Midewiwin ceremony."

Grand Medicine Society members believe all parts of creation are equal -- all things have a spirit. Humans are only a small part of the circle of life. They believe healing comes through prayer and from medicines the Creator placed in nature. The Midewiwin tradition dates back to long before the arrival of Europeans to North America. It was the fabric that wove communities together.

Midewiwin nearly disappeared after the U.S. government outlawed traditional ceremonies in the late 1800s. But many believe the Creator protected it.

Midewiwin is a fundamental part of following traditional ways, or walking the Red Road. A few will go through it at a young age. Many will wait until the spirits visit them. They may be invited through a dream, or by a Medicine Lodge member. Tony Treuer has been through the rituals. He says the ceremony is never shared with outsiders.

"Midewiwin is somewhat more guarded and closed than some other religious customs of the world. There's sort of a ritual death and rebirth that goes on. There's a lot of religious instruction. The giving of legends and songs," says Treuer. "But the substance of what is given is not divulged to someone until they actually go through the ceremony. And then they're told, 'You have to keep coming back here and helping out so that you can learn everything that we just gave to you.'"

| |||

Some people return every year, seeking spiritual rebirth.

Tom Stillday is considered a spiritual leader across the Midwest. He runs the Midewiwin Lodge in Ponemah. Stillday learned to perform the complex ceremonies by paying close attention to his predecessor, the late Red Lake spiritual leader Dan Raincloud.

A recording of Raincloud singing a medicine song to the Manidoo, or spirits, was made in the 1960s.

"I learned this medicine from one old guy at Leech Lake. When I sing this song, everybody listen to me. All Manidoo," Raincloud said before beginning the song.

Even people in Ponemah worry about the loss of language and spiritual tradition. When Tom Stillday was a child, there were perhaps a dozen men who knew how to run the lodge. Today, there are two or three.

But Stillday says the spirits will watch over Ponemah. He says he'll make sure the next generation carries on.

"My personal mission is keeping our culture alive, and I'm happy doing that," he says.

|

News Headlines

|

Related Subjects

|