|

Audio

Photos

Respond to this story

|

An "ugly" process

February 9, 2004

|

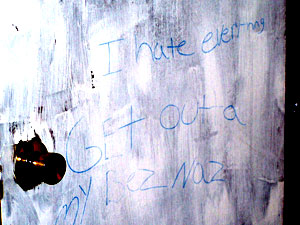

| "Don," 15, has bashed in his bedroom door. There are holes in the walls and nasty messages scribbled on the door and walls (MPR Photo/Tom Scheck) |

St. Paul, Minn. — Joseph is a lot like other boys his age. The 13-year-old likes to play with action figures and video games, and he loves sports. On this crisp, sunny Saturday afternoon, Joseph is happy playing hoops in his backyard. But Joseph is different than other children. He's a bundle of energy, constantly shuffling his legs, wringing his hands and jumping from room to room. He was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder at the age of four. The illness is becoming more difficult for his family to deal with because Joseph is getting more violent as he grows older.

"I was getting way too dangerous for my parents" Joseph said. "They weren't able to handle me. They couldn't handle me one more second. I was doing all of these bad things. I threw a book at my wall and dented a big hole in it. I was screaming at my parents...."

Joseph's parents didn't want his last name used for this story.

Over the last decade, Joseph has seen psychiatrists and tried different medications.

But none of the treatments worked the way Joseph and his parents hoped. He continued to break things and eventually threatened to hurt himself. His mother, Kris, says they decided to take him to the emergency room because he needed immediate help. Joseph was turned away from the hospital because there weren't available beds. Kris says they returned the next night insistent that their son get treatment. He was finally admitted.

"It's not a good process for the parents, for the kids," Kris said. "It's ugly at a time when you're needing the most support. Probably the hardest thing we ever had to do is bring our kid to the hospital and leave him there."

NO MONEY IN MENTAL ILLNESS

Joseph's experience is tragic, yet common, in Minnesota because psychiatric services are shrinking. The number of mental health beds decreased 15 percent between 1997 and 2001, according to the Minnesota Psychiatric Society. During that period, the same report says, demand for emergency and inpatient psychiatric services increased 50 percent.

One reason for the shrinking services is that many HMOs and state programs are not covering certain treatments. And even when they do cover the treatments, doctors and hospitals say the reimbursement rates are too low. That means hospitals are closing their behavioral health centers to focus on more profitable ventures.

The result? People with a mental illness are often put on long waiting lists. Some reports say it can take up to six months to see a psychiatrist.

Sue Abderholden, with the Minnesota chapter of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, says the system just doesn't work for kids like Joseph.

|

It's very hard to know how to work through that system or where you go for help and whoever that person was supposed to be, I never found them.

- Sharon |

"Instead of preventing a crisis from happening and providing services early, you have to have one to get to the head of the line," Abderholden said. "It would be good to put more dollars into the system to serve children earlier."

On top of that, Abderholden says the entire mental health system is confusing. The Minnesota Department of Human Services is supposed to make sure that those who need mental health services get them. But county and other local governments actually deliver the services. The courts, schools, public health departments and social service agencies also play a role. With so many places to go, Abderholden says people in need don't know how to navigate the system.

"There is no easy road map," Abderholden said. "We wish there was a Mapquest that you could click on to figure it out, but there isn't"

Eventually, Joseph received help at a residential treatment program in Bemidji. He's back home now and is attending the same school that suspended him for violent behavior. His mother, Kris, says he's doing better but she isn't happy with the way the system works.

"You have to keep following up on things," Kris said. "Especially with insurance and transferring records and things like that. A lot of things you think get done and they don't. When you're in the midst of a crisis, it's really hard to keep your wits about things. It's just a big burden to bear when you're at the worst time of your life."

WHO'S IN CHARGE?

Kris says she doesn't think she should have to pull the system together for her son to get treatment.

Michael Trangle agrees. He's an adult and adolescent psychiatrist for Regions Hospital in St. Paul. He says the system fails because there's no one group that coordinates care for a person with a mental illness. Trangle says people need treatment at the first sign of a problem.

"Everybody is working as hard as they can on the piece that they have but there's nobody there helping the family overall," Trangle said. "There's no one that says what should and needs to occur. We can and should get more of this service now and get you more of another service later."

| |||

A combination of a shortage of services and a confusing system means that the mentally ill often choose the easiest, yet most expensive resort, the emergency room.

That's how Sharon's son, Don, entered the system.

"Here's his room, you can see that I need to trade the door," Sharon said. "This is the fourth door that I've been through..."

Sharon's 15-year-old son, Don, repeatedly bashed in his bedroom door and walls. There's also nasty messages scribbled there. Sharon lives in the West Metro and also didn't want her last name used for this story. Her son has a string of diagnosed ailments: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, oppositional defiant disorder and reactive attachment disorder. She took her son to an emergency room several times after he acted in a violent manner. But as soon as he was stable, doctors released him with no follow up and no one to call.

"It's very hard to know how to work through that system or where you go for help and whoever that person was supposed to be I never found them," Sharon said. "I didn't find them at the hospital. I didn't find them through calling the intakes numbers. I worked with private therapists who would recommend trying different things."

GIVE UP YOUR CHILD, GET HELP

One suggestion was to file documents that would give up her rights to her son. Sharon was told that if she gave up her son to the foster care system, Don would be placed in a residential treatment center for kids with mental problems.

"I have no desire to give up my son," Sharon said. "He is my son and will always be my son. But he needs the care he has to get or his life will be a series of institutional options whether that's in a a prison system or some other system."

A report by the General Accounting Office says in 2001 more than 1,000 children were placed in Minnesota's child welfare system so they could receive mental health services.

Before Sharon gave up her custody rights, Don was arrested for breaking and entering. The judge ordered residential treatment of his mental illness.

In Sharon's case, she fought to get help for her son in Hennepin County. Since most mental health services are run at the county level, the situation could be better or worse in other places.

Glenace Edwall, with the state Department of Human Services, says her agency recognizes there are problems. She says a task force plans to propose some changes to improve the mental health system. Edwall says she'd like the state to create a uniform set of services for people with mental illness.

"The task force and the recent legislation were really a watershed event for recognizing that we've come so far with the children's mental health system and now it's time for the next leap. It's not so much as fixing it as saying it's really time that we take this seriously and build capacity statewide."

Critics, however, say there have been plenty of proposals but no real changes in the system. They say they doubt that conditions will improve until there's enough of a public outcry to force change.

|

News Headlines

|

Related Subjects

|